ARTicle is a feature curated by 3812 Gallery, presenting must-read articles by curators, scholars and art critics focusing on Eastern Origin in Contemporary Expression for your weekend digest.

In this week's ARTicle, we hope you will enjoy studying Shanghai artist Li Lei's abstract paintings through an essay written by Zhou Xian, Professor at the Art Institute of Nanjing University, first published in Li's catalogue Poetic Abstraction.

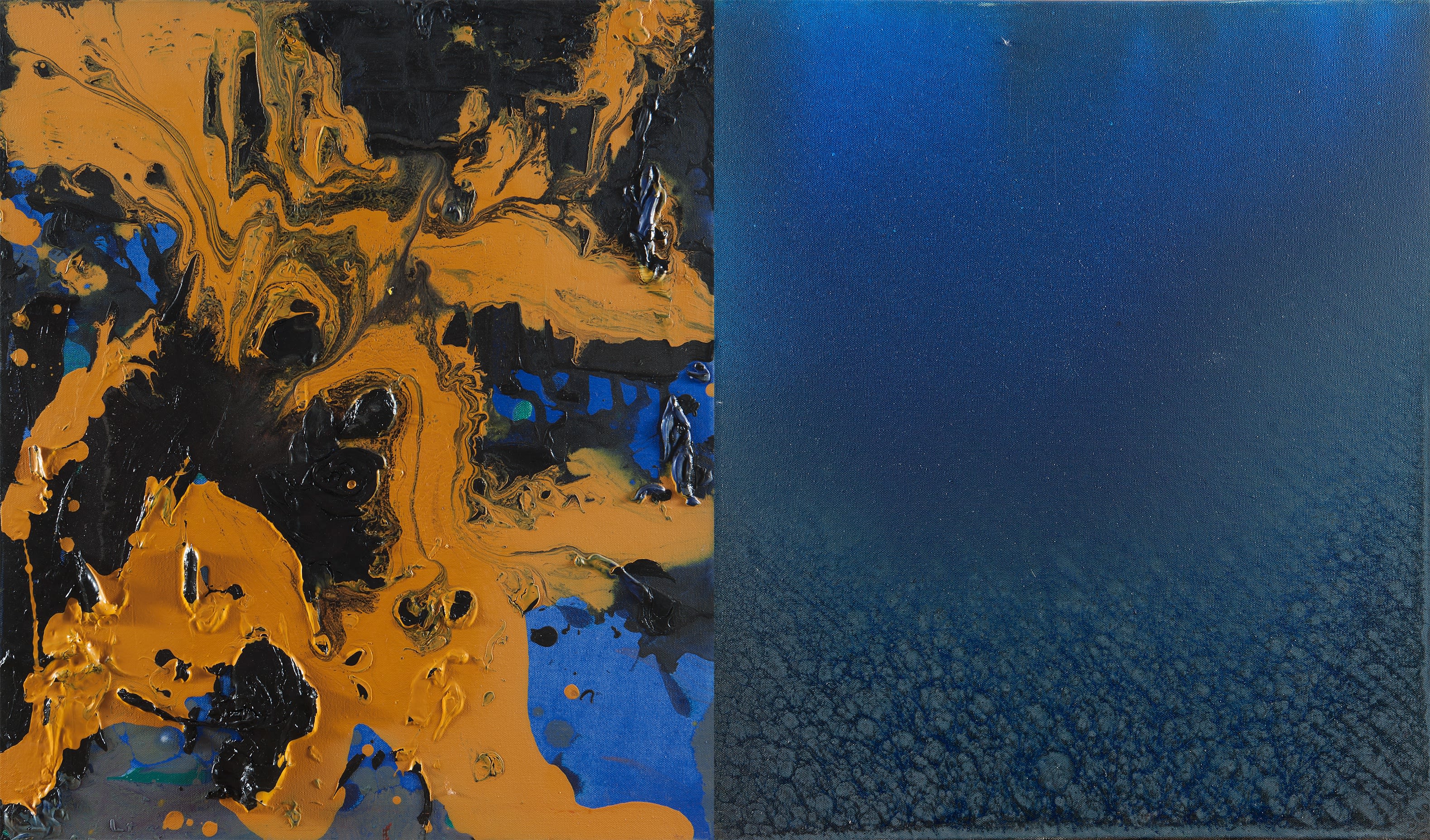

Li Lei, Calm Contemplation 6 - The Greenish River in Spring like Dyed by Bluegrass - Calm Contemplation 26, 2015-2019, Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 450 cm

The Metaphysical Meaning of Abstract Painting - An Essay on Li Lei

By Zhou Xian

The famous Tang-period poet Du Fu (712-770) has a well-known phrase, "The morning bell beyond the clouds is wet".Ye Xie (1627-1703) remarked on its seeming illogicality: "Sound has no form; how can it be wet? The sound of the bell enters the ears, and you hear it; how do you know the bell is wet? ... So, this poem conveys the wetness of rain: there are clouds, so there is rain; the bell is wet with rain ...The common Confucianist says it should read, 'The morning bell is beyond the clouds'. Or, it should read, 'The morning bell sounds beyond the clouds', and the word 'wet' has been supplied. But he does not know how to visualize the bell separated from him by clouds, or how to hear the wetness in the sound; mysteriously becoming aware, comprehending the real nature of things, and gaining access to this mental state." Here, Ye Xie is pointing to two completely different perspectives on the world: that of the poet and that of the common Confucianist. The former has a unique way of looking at the world, and like Du Fu experiences "mysteriously becoming aware … gaining access to this mental state." The common Confucianist, on the other hand, follows the herd and has an impoverished imagination; he cannot attain this state. In fact, this is one of the important reasons that art exists. If we combine Ye Xie's ideas with those of Leonardo da Vinci, we come to understand why art is art. Leonardo da Vinci said that art is "teaching people to learn to see". Du Fu's novel mental state, as in, "The morning bell beyond the clouds is wet", represents another perspective on Leonardo da Vinci's assertion that art is "teaching people to learn to see".

Different ways of seeing are key to creativity in art. Development in art has repeatedly shown that whether an artist can occupy a position in the history of art depends entirely on him or her finding a personal distinctive vision and conveying it to the public. I have carefully studied Li Lei's abstract paintings and feel that he has worked hard to condense his own vision of the world and to avoid common Confucianism. Such efforts make his abstract painting unique in contemporary Chinese abstract art.

Most artists who are drawn to abstract art and make a difference there, I have always held, have a psychological trait in common, that is, they tend to be philosophers. Compared to realist artists, abstract artists seem to process different visual experiences, and often to examine things with a philosophic style of visual probing, constructing the world with another kind of vision. In the creation of art, this philosophic temperament can be further explained as a visual metaphysics. In other words, artists with realist tendencies process immediate visual images, that is ordinary objects and people in the frame of reference of everyday life; whereas abstract artists process things beyond these ordinary objects or people, that is what is hidden, beyond the frame of reference of everyday life, existing at the level of mental concepts. In this sense, therefore, abstract artists are philosophers, who are less concerned with the images immediately before them, and rather wish to explore the hidden world of ideas behind visible everyday things.

I feel it is appropriate to look at Li Lei's abstractionist painting, as well as the art concepts he speaks of, from this perspective. Li Lei's abstract painting has its own unique psychological atmosphere. The general style of his abstract painting is obvious: although his works have varied from period to period, they all rely on variations on a basic melodic theme. Therefore, I would like to focus here on this basic theme of Li Lei's abstract painting-its general style. Before analysing Li Lei's work in detail, let us discuss the typology of abstract painting.

From the perspective of Western art history, abstract painting over its more than a hundred years of development can roughly be divided into a handful of types, including: Curvilinear, Colour-Related or LightRelated, Geometric, Emotional or Intuitional, Gestural, and Minimalist. If we interpret the works of Li Lei according to these types, however, we experience some difficulties, because Li Lei has attempted almost every style, with remarkable achievements. On the one hand, this shows that Li Lei's modes of practice in abstract painting are many, that his path is wide. He is eclectic in experimentation with varied forms of expression. On the other hand, it indicates that his abstract painting draws extensively on the experience of his predecessors and works hard to explore an artistic style rich in individual traits. From Li Lei's many decades of abstract painting, I think it is possible to sum up some of the personal features of the "Li style".

First, he rejects geometric abstraction, avoiding the regularity of geometric shapes, colour blocks and lines in his works, and exploring a more random, fortuitous and transient abstract style. From the point of view of the history of art, the geometric style is a kind of art that brings with it rational colours and intellectual games. From Malevich's Suprematism to Mondrian's Neoplasticism, on to the Elementarism of van Doesburg and so on, instances abound. Li Lei may deliberately avoid geometric style, with its scientific and rationalist character, or perhaps his choice of abstract style originated in his own personality or temperament. From a psychological point of view, style trends are not only the product of the artist's active choice or exploration, but also the natural externalization of his inner spiritual qualities. Taking an overview of Li Lei's works, I think he is attempting a more random, improvisational and fortuitous abstract art creation path. A typical feature is his emphasis on the process of art; as Hemingway said, "Everything is discovered in the process." From the perspective of the typology of abstract art, this style is more emotional or intuitive, pays greater attention to the expressiveness of images rather than composition, and emphasizes the discoveries and changes inherent in improvisation. This breaks free from the stereotyped practice of "imitation", and offers the abstract creative process a focus on action and expression. I noticed a photograph of Li Lei painting in his Water to Water album: the artist is prostrate on the canvas on the ground, using powerful arm movements to create a composition of flowing colour blocks. This movement, full of hinted meanings, demonstrates that Li's style of painting has a clear tendency towards gesture-oriented "action painting", with the "performativity" characteristic of recent aesthetics. The style reflects the artist's greater focus on emotion and expression. Compared with Pollock's action painting, Li Lei seems to emphasize the unconstrained, improvisational features of traditional Chinese painting; just as in ink painting it is the movement of the brush and ink-wash on paper that is generative, so this Chinese tradition is channelled into Li Lei's abstract painting. As a result, Li Lei goes further than Pollock; in the context of his art, the painting is already like a traditional theatrical performance, except that the movements are not stylized as in the classical opera, but have a natural and unconstrained expressivity.

Secondly, although the painting language and means of expression in Li Lei's abstract paintings are extremely rich, I notice a dominant visual grammar. In his analysis of artistic styles from the Renaissance to the Baroque, the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin found that Western art demonstrated a shift from "linear" to "painterly". Specifically, this is apparent in the change from Albrecht Dürer to Rembrandt. Although Wölfflin's linear-painterly dichotomy relates to realist painting, I think it actually represents a conflict in all kinds of painting, including abstract. According to Wölfflin, the linear style focuses on the reality and outlined edges of objects, whereas the painterly style ignores outlines and rather emphasizes a visual impression of the shape. "These two styles represent two ways of perceiving the world; they are different in terms of aesthetic taste and interest in the world, yet each produces a perfect picture of the visible." Wölfflin's linear-painterly binary concept also offers a perspective for the consideration of abstract painting. In other words, in abstract painting, there are two different trends owing to divergent artistic approaches. One can be summed up as line-led abstract painting and the other as a block-led abstract painting. Examining Li Lei's abstract paintings from this point of view, I find a relative balance. His abstract paintings can be divided into two categories, one block-led, the other line-led. In works of the former category, such as the representative Shanghai Flower series, large blocks of colour occupy most of the composition; lines either disappear altogether, or have a minor, secondary role. This type of "painterly" work has great visual impact, especially in the use of contrasting colours in different colour blocks, resulting in a tension between cool and warm colours; in the painting A Sprout on the Branch of March, a tension is set up between colour blocks in different shades of red and blue, which against the background of grey is particularly arresting. Li Lei's bold use of colour in his painterly works, with tension between the colours, and variation in the shape of the colour blocks, is highly impressive. This feature is most evident in the Shanghai Flower series 72, 73, 95, and 96, as well as in the Amongst the Ultimate Deep series; these works, in their unique style, make up a "family". In contrast, in the line-based "linear" paintings, such as the Zen Flower series, lines against light grey backgrounds compose varied groups, intertwined with each other, expressing a sense and state of Zen in their motion in tranquillity. Unlike the outlines of realistic painting, in these works the lines have an independent and expressive quality. In Flow Between heaven and Ocean series, some curves are sketched out against a strong colour background. In the Listening to the Cicadas series, just a few white lines cross the greyblack background, expressing the penetration of the Zen void. In Li Lei's rich and varied abstract paintings, block-led and line-led represent different paths of artistic expression. In my personal viewing experience, I prefer the large block-led paintings: the huge colour blocks control the atmosphere of the paintings, and convey the artist's refined inner visual metaphysical concepts. He has a distinct "Li style", and especially in Amongst the Ultimate Deep series, takes this style to the limit, with the colour blocks blurring, converging, contrasting and conflicting, in every conceivable way.

Li Lei, Shanghai Flower No. 21, 2008, Oil on canvas, 180 x 150 cm

Li Lei, Zen Flower - Pink, 1999, Oil on canvas, 100 x 100 cm

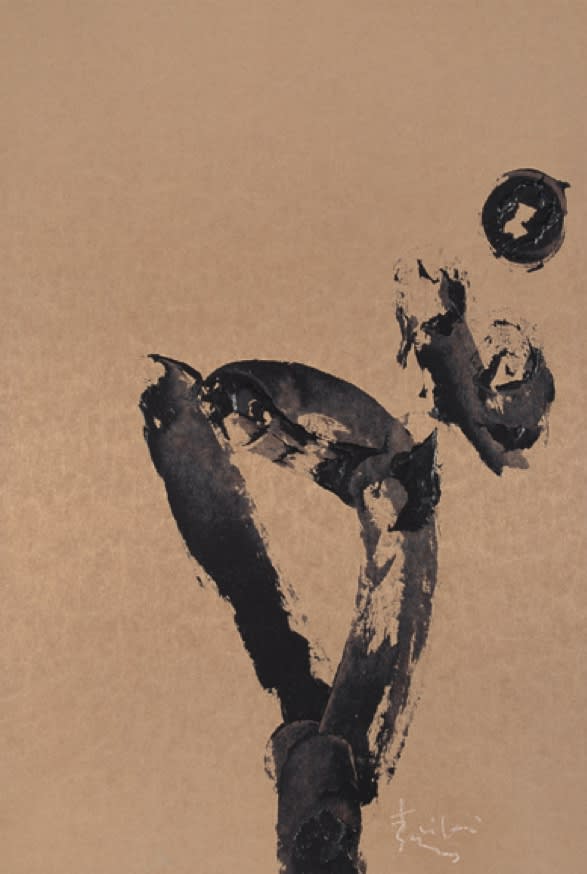

The third aspect of Li Lei's work that has provoked my interest is his series of traditional Chinese-style black-and-white ink paintings. In the science of colour, neither black nor white is classified as a colour. Traditional ink painting transforms the mystery and spirit of the world into black and white. Although oil painting is a kind of painting from the West, and its techniques belong to Western culture, nonetheless, as a Chinese artist, Li Lei understands his own traditional philosophy and culture, and some native elements have seamlessly entered his abstract painting language. Of course, artistic and value judgments about abstract painting cannot be based on ethnicity or ethnic factors. The important question, I think, is how this indigenous art, as a (kind of) background or atmosphere, gains a foothold within the entirely Western (tradition of) abstract painting, and brings about some noteworthy changes. In Li Lei's series The Browns and The August, there are some bold experiments and innovations. On a plain brown background, or just a piece of natural canvas, the black of the large brushstrokes sweep past with great force, leaving dynamic calligraphy-style marks, in contrasting black and white, solid and void, dark and light. Seemingly random black colour blocks or strips, of varying widths, are intertwined, the ink diffusing in all directions, to create a feeling of movement in the painting, like a set of determined melodies rising briefly. Li Lei may have studied the Black-and-White Series of American Abstract Expressionist painter de Kooning. De Kooning, inspired by Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, created a group of purely black and white abstract paintings; but these works are still clearly Western, without the spirit and penetration of Chinese ink painting. In contrast, these two series by Li Lei are clearly essentially different to de Kooning's works, in that the paintings are imbued with the mood typical of ink painting. Even more interestingly, in the The August series, the [traditional] method of leaving a space is also introduced to abstract painting-a large area of natural canvas is left empty. Looking at this interesting group of Chinese-style works, I even recall the words of Mi Fu (1051-1107), one of the Four Masters of the Song Dynasty:

Haiyue (Mi Fu) was summoned on account of his knowledge of calligraphy as a court academician, and the emperor asked about his acquaintances in the generation famed for calligraphy of the current dynasty (Northern Song). Haiyue spoke individually of people: "Cai Jing fails to master the brush, Cai Bian masters the brush but with a lack of ease, Cai Xiang restrains his characters, Shen Liao orders his characters, Huang Tingjian draws his characters, Su Shi paints his characters". The emperor then asked about the nature of his subject's (Mi Fu's) calligraphy: "Your servant brushes his characters."

The phrase, "Your servant brushes his characters," fits as a description of these two series by Li Lei; his works have something of Mi Fu's style of "brushing characters", conveying a whole mood in just a few strokes.

Li Lei, The Browns 03, 2002, 60 x 40 cm

Willem de Kooning, Black Untitled, 1948,

Oil and enamel on paper, mounted on wood, 75.9 × 101.6 cm

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Li Lei, Between Clouds and Water Series 5-11, 2012, Acrylic on canvas, 50 x 40cm

At this point, let us return to conceptual issues relating to abstract art. As already mentioned, abstract art has a kind of inherent spiritual character, so the painter who loves abstract art has some natural affinity for visual metaphysics. While, on the one hand, Li Lei is very knowledgeable about Western art, especially modernist art and abstraction-indeed he has written many articles reviewing Western artists; on the other, he is also well-versed in Chinese traditional culture, and has an especially strong interest in Buddhist philosophy. This kind of thinking and creativity, based in the zone of overlapping and intermingling between Chinese and Western cultures, often leads artists to look at the world using a multiplicity of ideological resources. I find that Li Lei is not only an artist of the senses, but also a philosophical artist, who in his artistic exploration sees great themes in small subjects, and can focus on many overarching "grand narratives". In the context of The Apsara's Flowers, Li Lei states frankly:

For many years, I have been thinking about certain questions. Some of humanity's questions the sages have answered; others we are still exploring. In human investigation of questions there are no more than two main paths: the first based on the science of reason, and the second based on the perception of intuition. Art focuses on intuition, so the answers given by art can often not be quantified, and there is much ambiguity. Precisely because of this ambiguity, there are many opportunities for the involvement of all kinds of artists, and the room for manoeuvre is large. This is the charm of art.

The main questions that I think about are: 1. the origin and evolution of the universe; 2. the relationship between the spiritual and the material; 3. the relationship between time and space; 4. The composition of life; 5. life of the individual life and life of the group; and 6. spiritual power and dissemination; 7. life in other places and times; 8. self-expression and liberation of the self; 9. Sensory language and transmission of the spirit, and so on.

Of course, the artist's way of thinking is not like the deductive or speculative thought processes of scientists or philosophers. Rather, it is an exploration by means of his or her own artistic language and style. Any "grand narrative" ultimately turns into the "small narrative" of a specific artistic language. However, it is worth reminding ourselves that the artists who have grand narrative concerns are different from the artists who do not have these concerns, and their artistic works have a different feel. Li Lei's major concerns have been translated into the creating and exploring the language and style of abstract art. In his abstract paintings, nature, life, society, history Of course, the artist's way of thinking is not like the deductive or speculative thought processes of scientists or philosophers. Rather, it is an exploration by means of his or her own artistic language and style. Any "grand narrative" ultimately turns into the "small narrative" of a specific artistic language. However, it is worth reminding ourselves that the artists who have grand narrative concerns are different from the artists who do not have these concerns, and their artistic works have a different feel. Li Lei's major concerns have been translated into the creating and exploring the language and style of abstract art. In his abstract paintings, nature, life, society, history and the self are integrated into one. Through colour, line, shape, shading, and composition, a quest like the "Questions to Heaven" of the poet Qu Yuan (c. 340-278 BC) is effectively conveyed. In my opinion, these grand narrative concepts elevate the artist to a visual metaphysical level, to the most experiential and intuitive artistic sensibility, incorporating philosophical problems in its intrinsic weightiness and depth. They make his abstract paintings complex in their concision, incorporating historical depth in their planar composition, thus creating for the viewer more mental associations and enlightenment. The philosopher Nicolai Hartmann has suggested that any artwork presents a system made up of different levels. The greater the work of art, then the deeper the levels extend, but not every person appreciates all the levels. For example, drama, starting from vivid performance, lines of the script, and psychology of the characters, through twists of fate and ideas of personality, finally reaches a conception of humanity. And music, starting from the level of direct hearing of resonance, progressing through the level of inner feeling produced by the melody, ultimately achieves the metaphysical level, the highest level of things. When I view Li Lei's abstract artworks, I often become aware of rich visual metaphysical implications behind the paintings. These implications represent both those already fully apparent to the artist, and those questions to which he is seeking as yet unknown, but hard sought after answers.

Returning to the argument I put forward at the beginning of this article, abstract artists have something of a philosopher's temperament: this is what I appreciate in my viewing of Li Lei's abstract paintings.