Hsiao Chin, Light of Divinity-16, 2017, Acrylic on canvas, 110 x 180cm

ARTicle is a feature curated by 3812 Gallery, presenting must-read articles by curators, scholars and art critics focusing on Eastern Origin in Contemporary Expression for your weekend digest.

In this week's ARTicle, we are delighted to present the essay Hsiao Chin: A Fundamental Sense of Hope written by British award-winning art critic Richard Cork for the exhibition catalogue of Hsiao Chin's retrospective In my beginning is my end: the art of Hsiao Chin, which takes place at the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Latvia from 31st July to 25th October 2020, as part of the celebratory programme for the artist's 85th year. In the essay, Richard Cork develops from Hsiao's early works from the 50s and walks you through the extraordinary sixty-year oeuvre of the post-war abstract master of the East.

Hsiao Chin: A Fundamental Sense of Hope

By Richard Cork

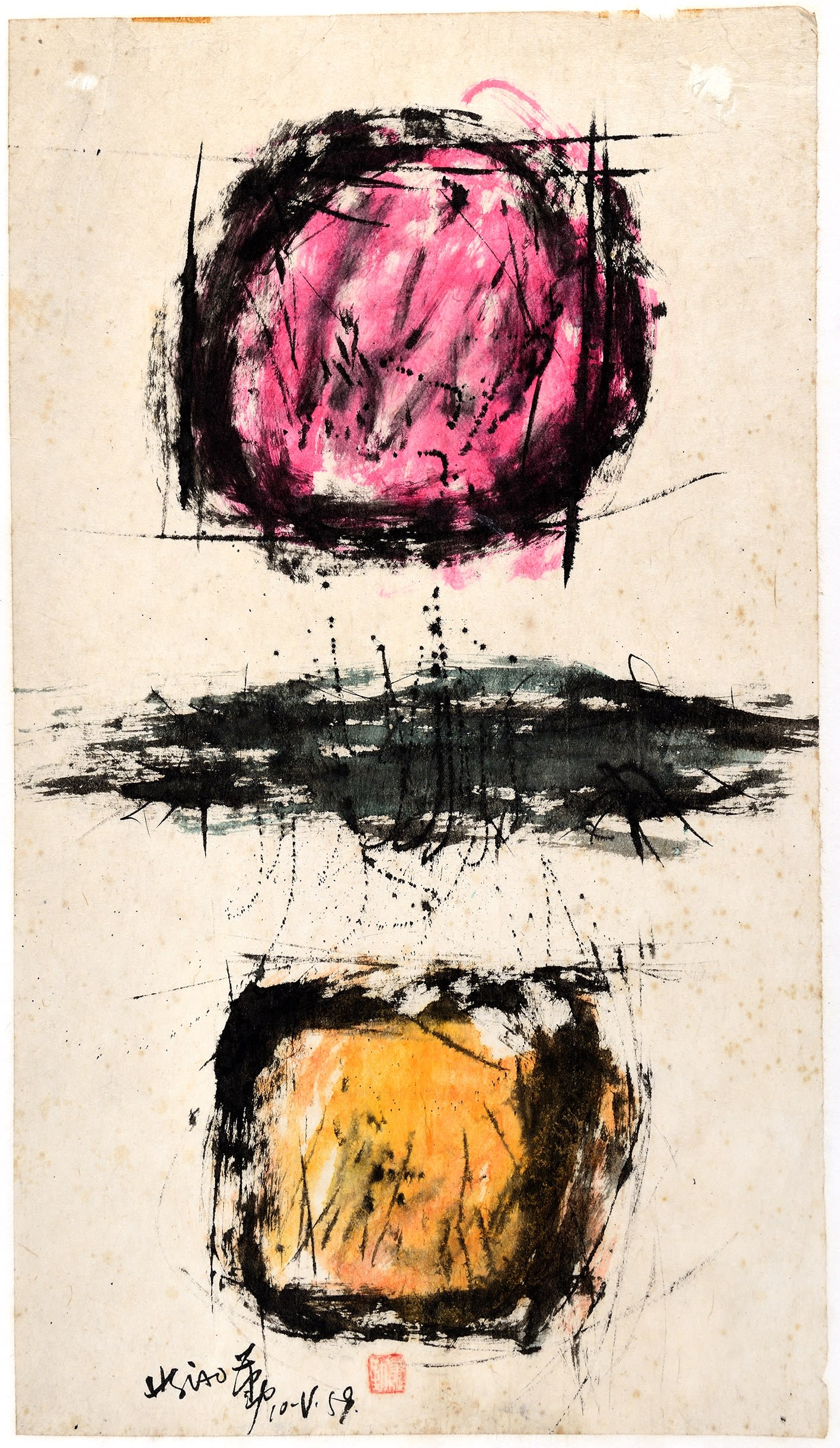

Even near the beginning of his long and inventive career, the young Hsiao Chin was able to grasp his overall priorities as an artist. In 1959, soon after deciding to engage with the vitality of radical art events in Italy, he executed a freely brushed canvas called ‘Pintura - AO’. Although it is handled in a looser way than most of his subsequent work, this vigorous image seems dedicated to exploring simplification and searching for essential form. The brushmarks are very bold, and in the same year he deploys ink on paper to make the radically purged ‘Untitled - 16’. Here, two brightly coloured forms are suspended like planets in space, separated only by a dark mass at the centre. Hsiao Chin’s search for an elemental vision is already evident.

Hsiao Chin, Painting - AO, 1959, Oil on canvas, 65 x 55 cm

Hsiao Chin, Untitled - 16, 1959, Ink on paper, 57 x 32 cm

Many years later, he looked back on his approach and declared: ‘Since a very young age I have always been sceptical about life and felt the need to explore and investigate.’ By 1961 he was determined to discover the eloquence of extremely simplified forms. In a large painting called ‘Dive’, most of the picture-surface is reduced to a single colour. Only at the base of the canvas does a glowing and reductive circle float above a horizontal bar of black. ‘Crouch’ achieves a similarly purged goal in the same year, although brilliant orange is now the paramount colour. The dark forms suspended at the top look almost vulnerable compared with the boisterous and massive orange sun blazing at the very centre of another 1961 painting, ‘Love of Spring’.

Hsiao Chin, Dive, 1961, Acrylic on canvas, 140 x 110 cm

Hsiao Chin, Love of Spring, 1961, Oil on canvas, 90 x 70 cm

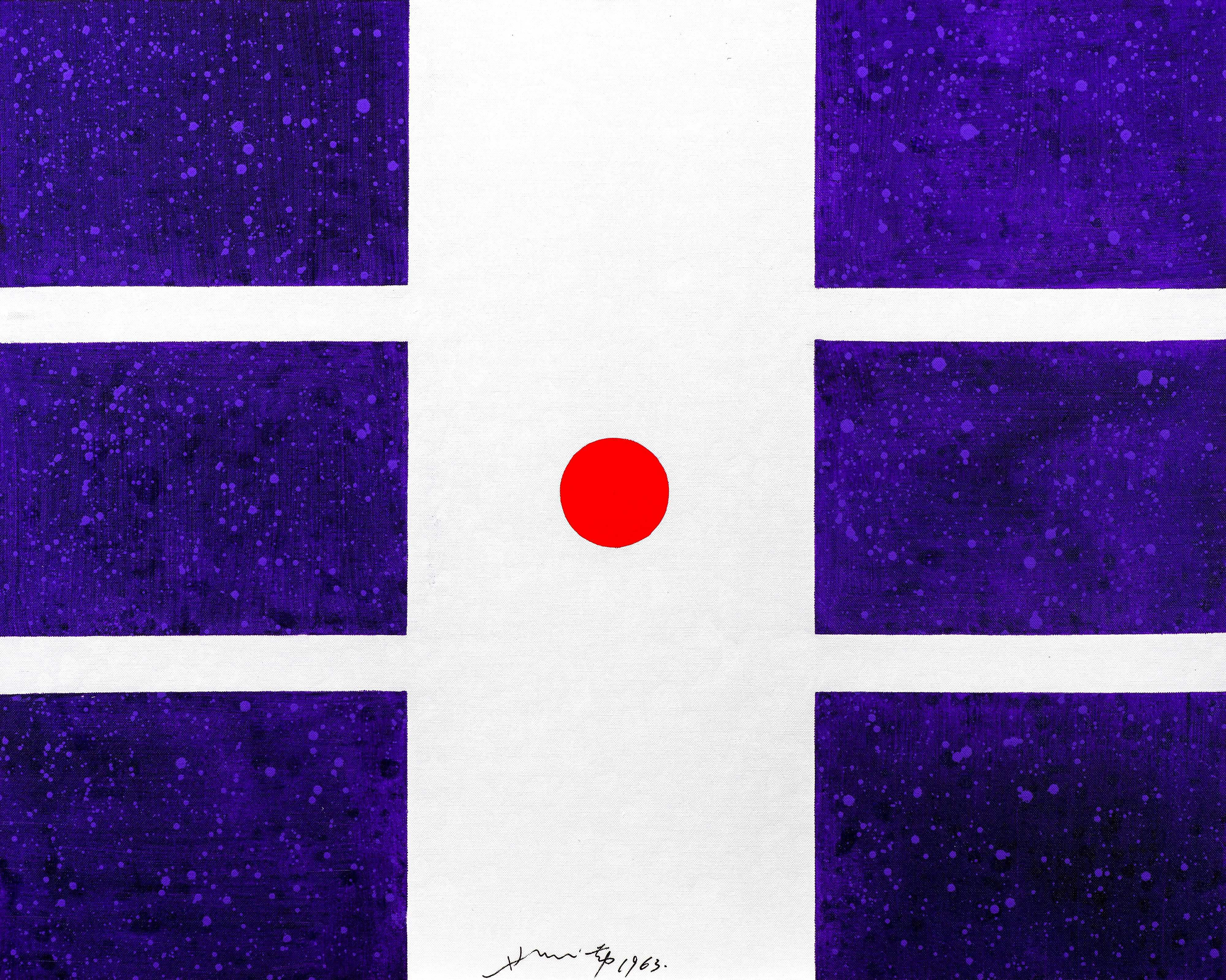

All three of these paintings were made while Hsiao Chin was in transition towards Punto, the international art movement launched in Milan. He became one of its founders, and the black forms in ‘Love of Spring’ take on a vivacious life of their own. In 1962 two paintings, executed with ink on canvas, investigate ‘The Origin of Chi’. The black strokes resemble gigantic brushmarks, deployed with exceptional verve. They seem to be either rushing towards or escaping from a small, brightly coloured form, but the following year Hsiao Chin stabilized everything in a grand acrylic painting called ‘Great Earth’ where everything is marshalled with a sense of absolute finality.

Hsiao Chin, The Origin of Chi-3, 1962, Ink on canvas, 40 x 60 cm

Hsiao Chin, Great Earth, 1963, Acrylic on canvas, 80 x 100 cm

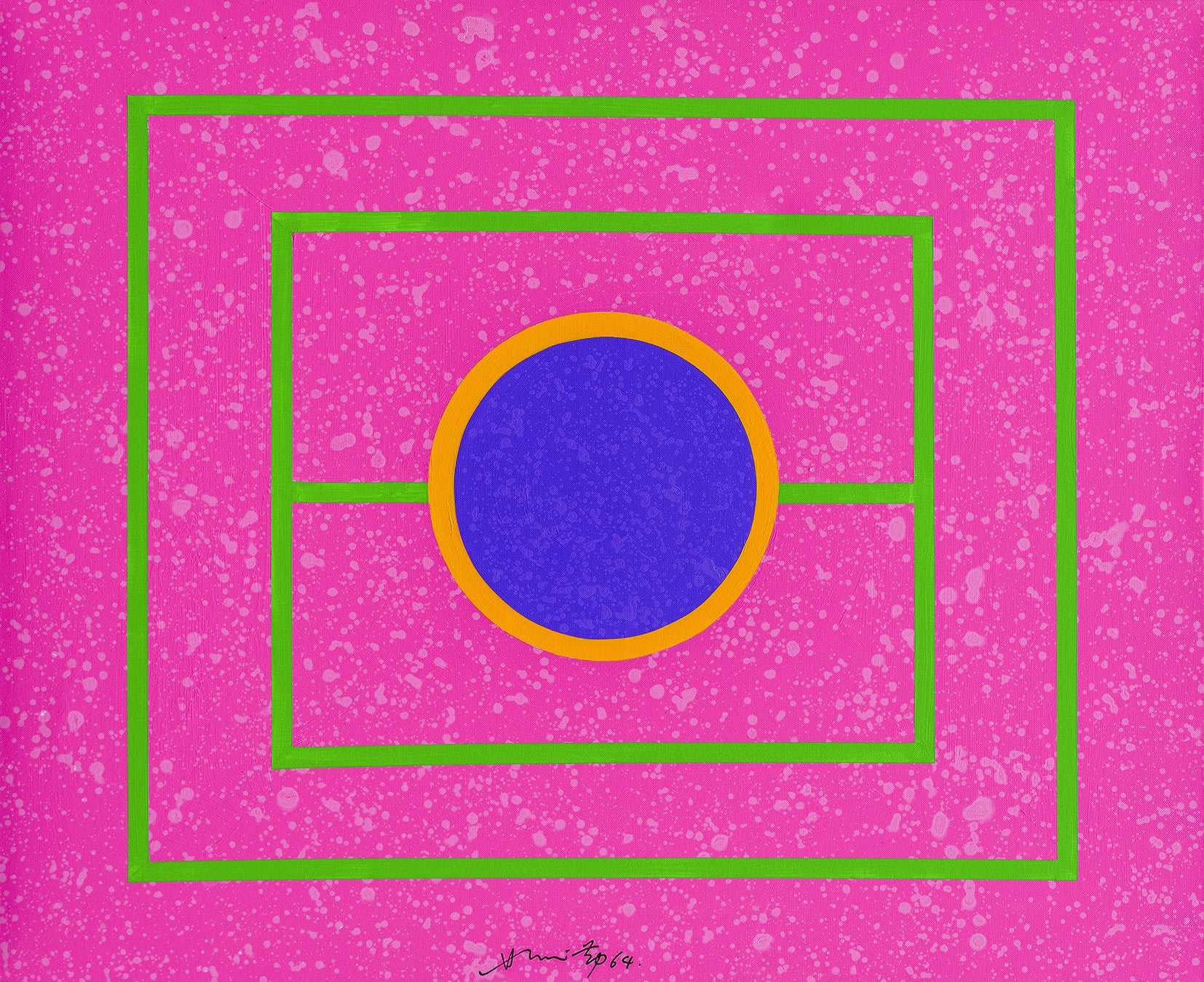

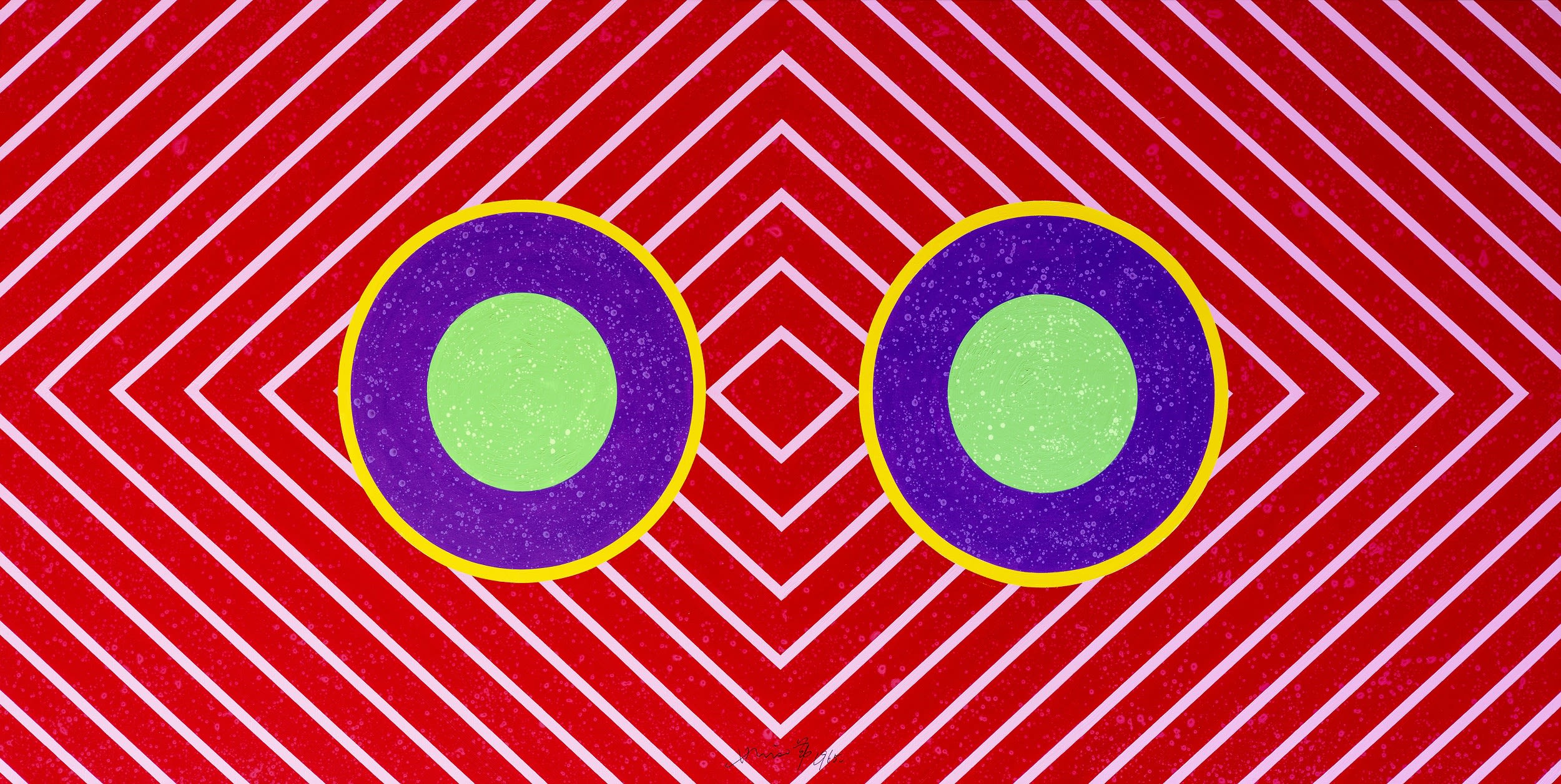

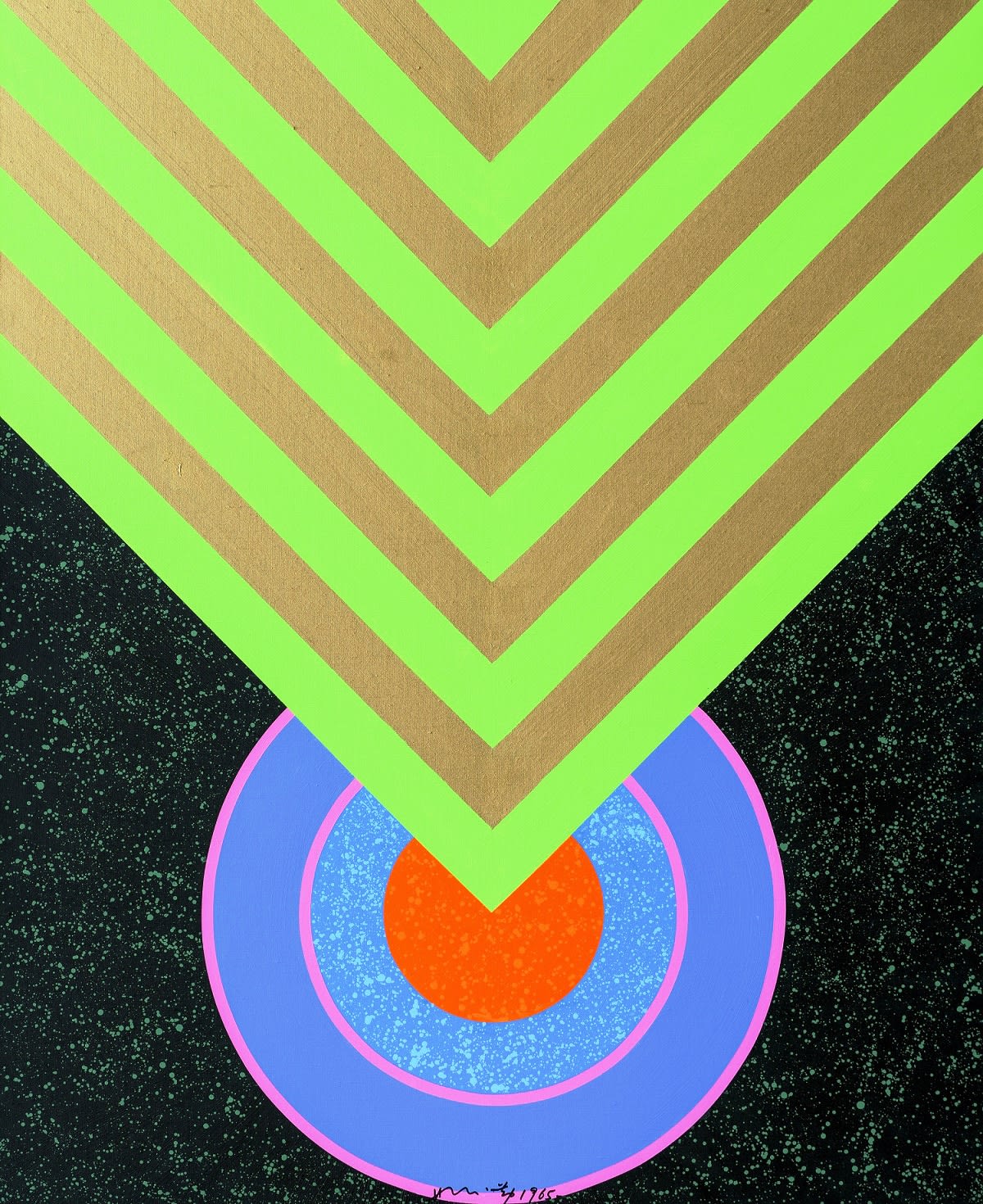

Balance of a different kind courses through ‘Parallelism of Tao’, and in 1964 an immensely assured stability reigns in ‘Latent’. The circular shape at its centre appears held in balance by a surrounding green structure, and this sense of confidence is even more pronounced in ‘La Vibrazione del Sole’ (The Vibration of Sun). By this time he had been given a large exhibition in Paris, and compositional energy pulses across a dynamic, thrusting acrylic painting aptly called ‘Power of the Light’ in 1965. The Punto movement was nearing its end, but Hsiao Chin now chose to work on monumental canvases like ‘Vibrazione Universale’ and ‘Universal Vibration’. The fierce diagonal lines shooting across these acrylic compositions are alive with certitude, and by 1966 he felt ready to spend four months in the US. A spirit of exuberance dominates the freely handled ‘Heavenly Secret’ as well as ‘Energy of Movement’.

Hsiao Chin, Latent, 1964, Acrylic on canvas, 90 x 110 cm

Hsiao Chin, Vibrazione Universale, 1965, Acrylic on canvas, 140 x 290 cm

Hsiao Chin, Power of the Light, 1965, Acrylic on canvas, 160 x 130 cm

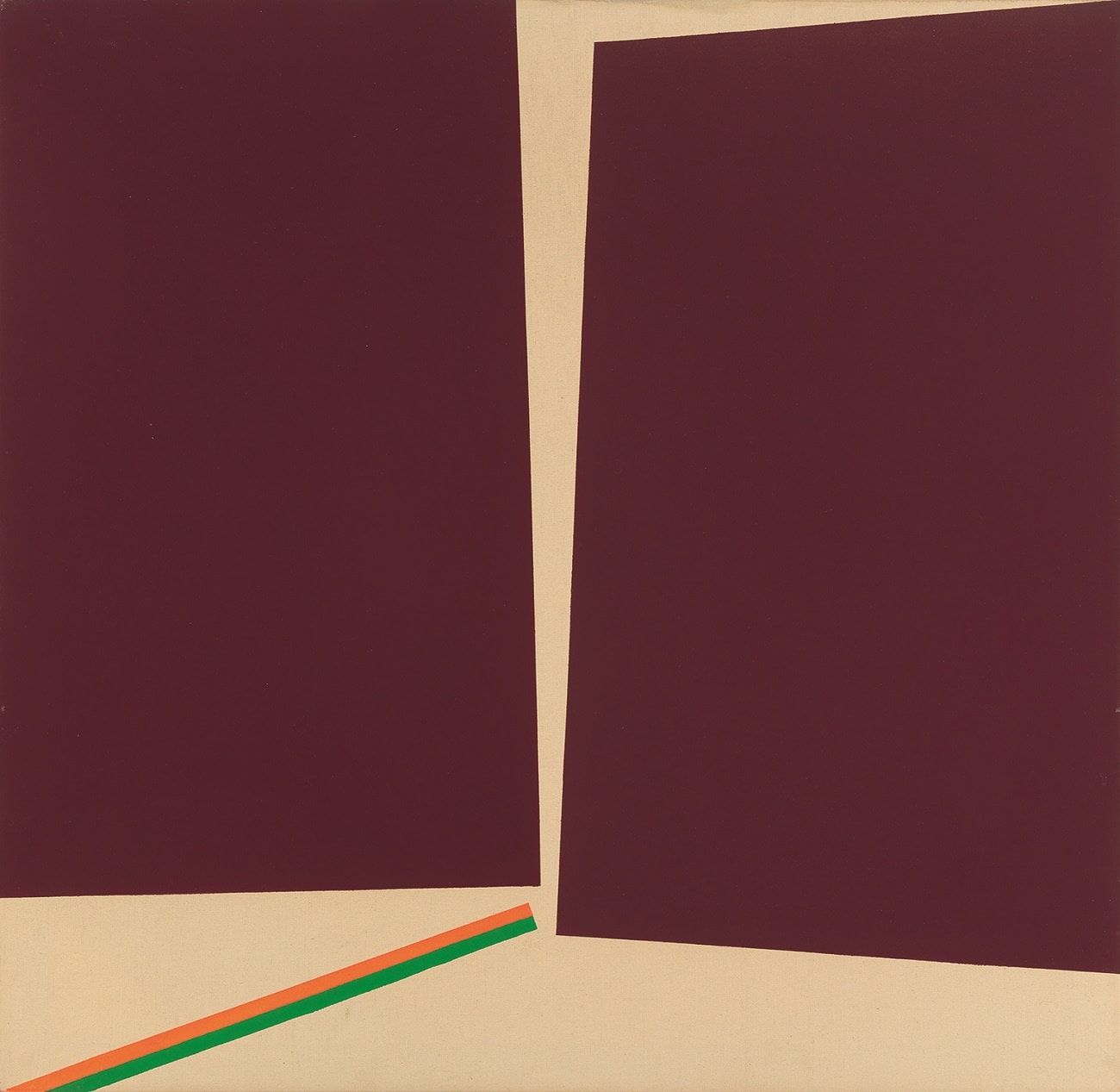

Around this time, he alternated between employing deliberately broken brushmarks and adopting the very different approach visible in paintings like ‘Nero’ and ‘Tension - VI’, where smoothly finished blocks of colour dominate the canvas.

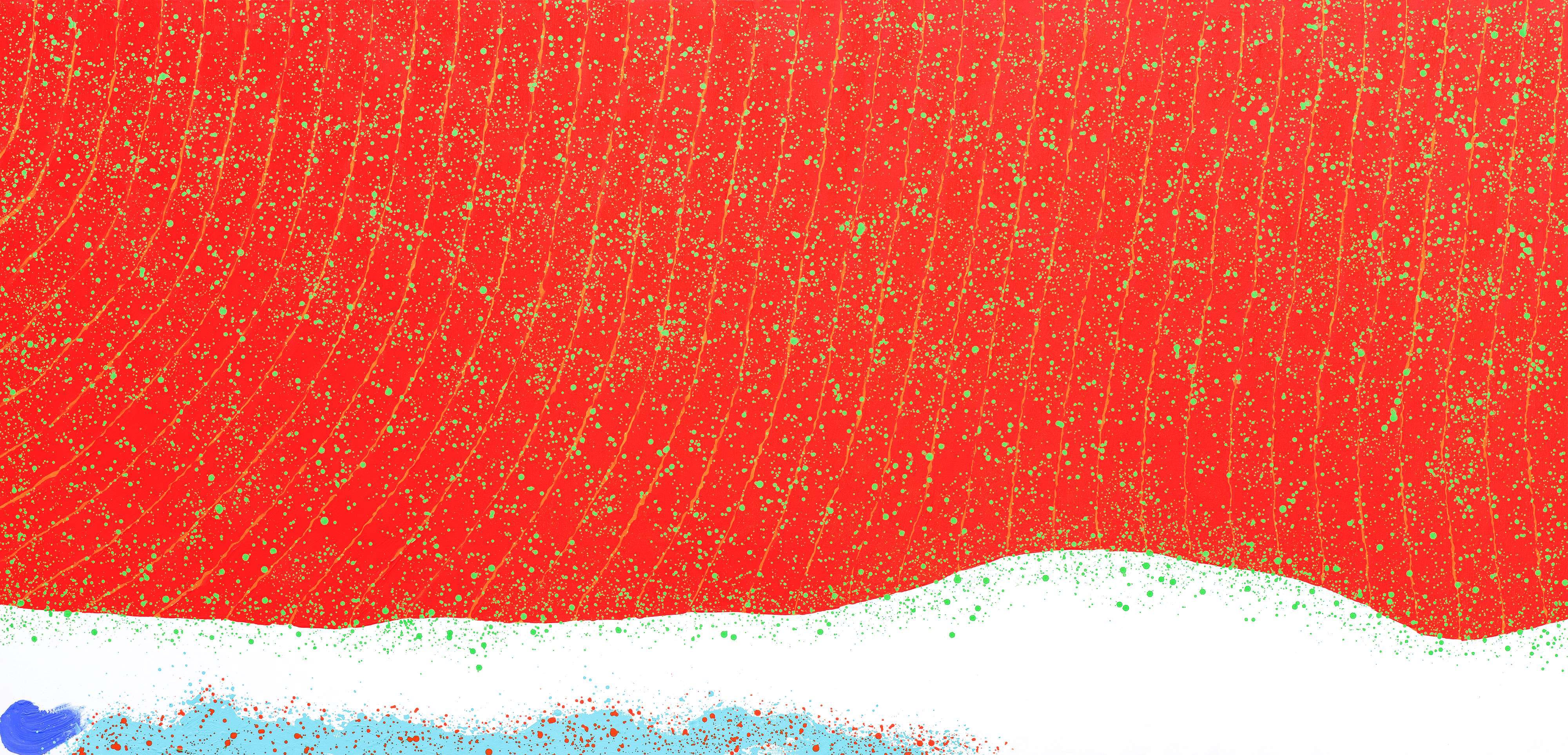

An increasing awareness of the cosmos can be found as Hsiao Chin worked his way through the 1970s. In ‘Movement’, a brightly coloured beam shoots horizontally across an otherwise dark immensity. And during the subsequent decade this mysterious space is filled with dramatic encounters. ‘Beginning of Chi - 2’ pulsates in front of our eyes, as three blood-red forms are arrestingly juxtaposed with black matter below. In between, tiny multitudinous spots of acrylic punctuate the canvas, and a similar restlessness courses through ‘Chi - 156’ the following year. By 1985 Hsiao Chin found himself ready to unleash the vivacity of ‘Great Chinese Dragon’, where a dazzling mixture of red, yellow and green acrylic undulates across an otherwise empty space while darkness lurks ominously at the summit.

Hsiao Chin, Beginning of Chi-2, 1983, Acrylic on paper, 85 x 186 cm

The terrible tragedy of his daughter Samantha’s death, in 1990, affected Hsiao Chin so profoundly that he felt unable to paint for almost a year. Recovery began when his sense of grievous loss gave way to a redemptive focus on paradise. An unusually large painting called ‘Transcending the Eternal Garden - I’ envelops us in warmth, and the same spirit of reassurance dominates the second canvas in this major 1993 series. The vortex-like circle dominating ‘Energy of Infinity Horizon’ is equally impressive, and an even wider painting in 1997 heralds the ‘Il potere dell’Universo Nuovo’ (Power of the New Universe). He places his daughter within paradise in ‘Samantha nel giardino eterno’, as this deeply consoling title makes clear.

Hsiao Chin, Transcending the Eternal Garden-1, 1993, Acrylic on canvas, 140 x 280 cm

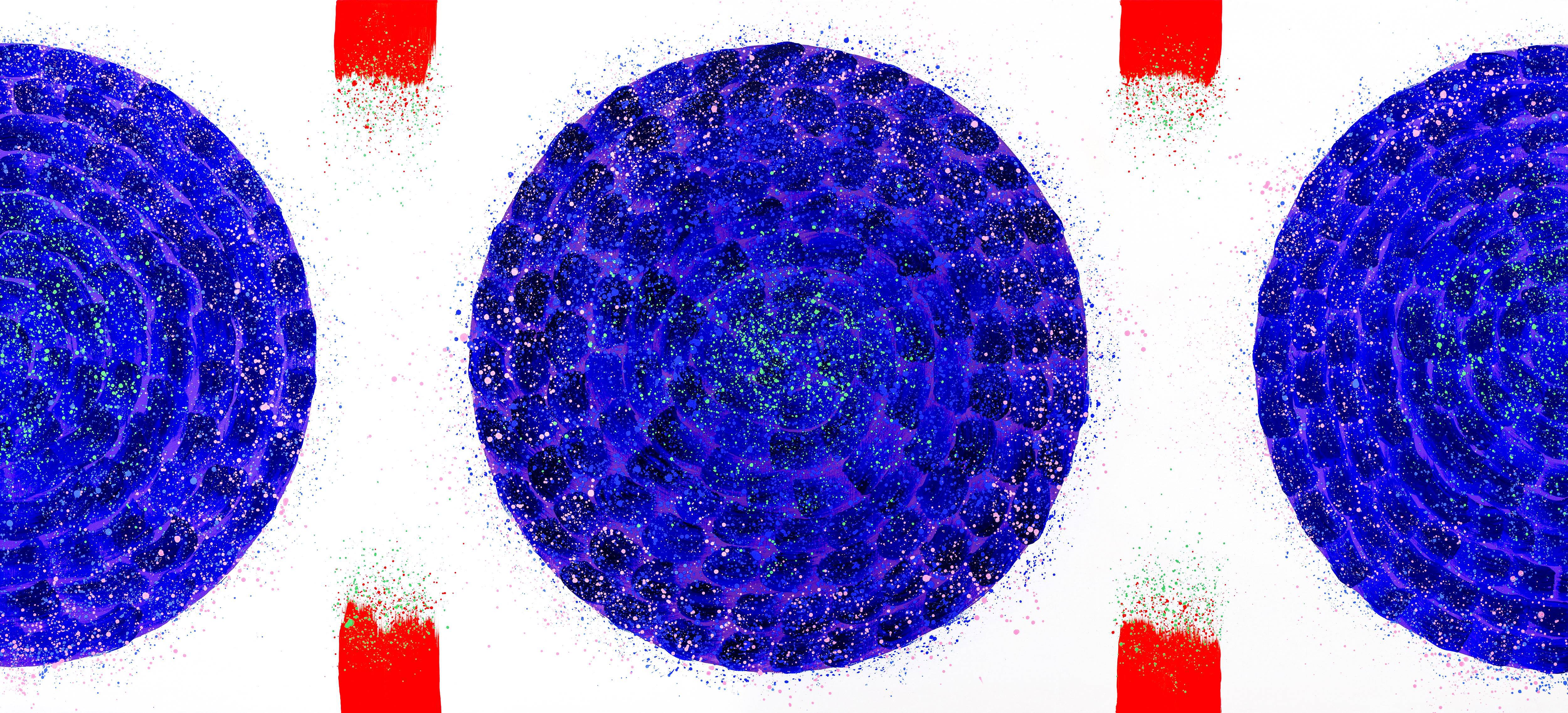

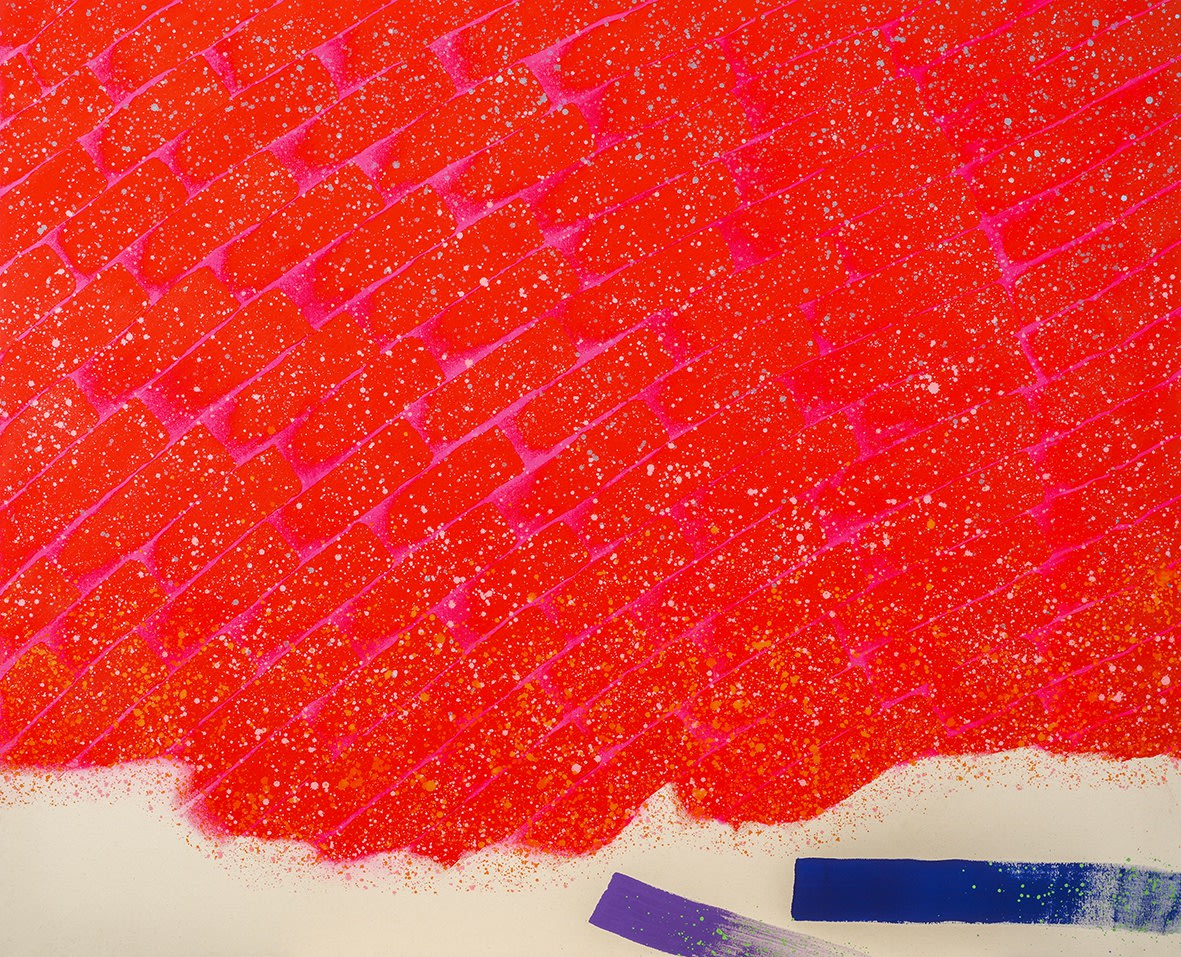

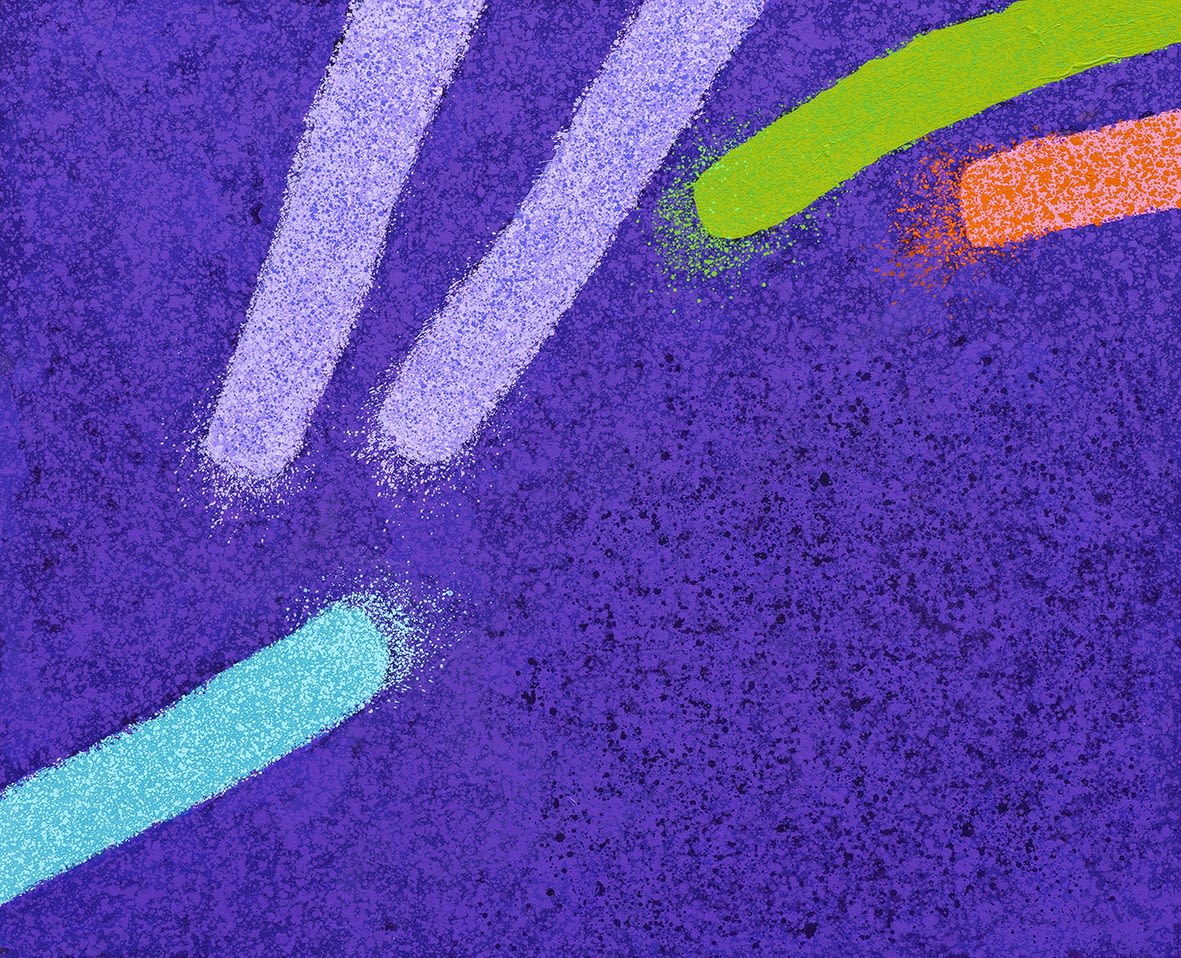

The advent of a new century is proclaimed in a 2000 series entitled ‘Samadhi’, which ranges from shimmering redness to darker yet no less resplendent colours. ‘Blue Introspection’, a mosaic glass work commenced in 2007 and completed eleven years later, explores a more melancholy mood. But ‘Communion’ is a painting alive with eager forms responding to each other’s vibrancy, and in the compelling ‘Light of Divinity - 16‘ Hsiao Chin affirms his fundamental sense of hope by sending a spectacular beam of brightness through even the darkest and most mysterious realm imaginable. This spirit of visual revelation shows just how significant his contribution to European abstract painting really was. He played a truly distinctive role in its dramatic, sustained and adventurous development.

Hsiao Chin, Samadhi-39, 2000, Acrylic on canvas, 130 x 160 cm

Hsiao Chin, Communion, 2010, Acrylic on canvas, 130 x 160 cm