For this edition of ARTpiece we will explore the abstract expressionist style of Modern British artist Albert Irvin OBE (RA), and Chinese contemporary abstract artist Li Lei. Their works are widely collected and exhibited in world-renowned museums, such as Tate Britain (London), the Victoria and Albert Museum (London), National Art Museum of China (Beijing) and MGM Cotai Chairman Collection (Macau).

Although born many thousands of miles apart, their celebratory use of bold colours and uninhibited brush strokes to explore the theme of nature, unites the two artists. We will focus on Irvin’s ‘Patmos, 1987’ and Li’s ‘Mad Water-20’ and in particular the artists use of colour and brush techniques.

‘I would like to feel that it is possible to dispose the elements of a painting as in a piece of music.’

– Albert Irvin

Albert Irvin OBE (RA) was hugely influenced by ‘St Ives’ artists, such as Sir Terry Frost and in particular the works of Peter Lanyon. His familiarity with maps, acquired during his time in the air force in the second world war, and seeing the ground from the air, laid out as a flat expanse, stimulated his thoughts about his use and direction of marks on the canvas. Though they at first seem carefree, the directions and use of these marks was considered, evoking a sense of space and travel through which Irvin explored the urban environment he experienced on a daily basis. Irvin eventually moved away from these figurative sources of inspiration for his paintings, and as his good friend Basil Beattie explained, Irvin 'recognised he was searching for a language that wasn't dependent on looking and seeing and strove towards other aspects of human experience'.

In Patmos, the reference to Irvin's early figurative influences is still clear in the bold, grid like lines of the painting, whilst the splashes and gestural brush marks of his unconscious mind traverse the canvas in his developing abstract expressionist style. The music that was so vital to Irvin, helping to sustain his rigorous work routine, is present in the rhythm and flow of the painting. The intense painterly style and many layers of pigment epitomise the idea of painting as the expression of the life force within the space of the image. Irvin's works are a canvas of his hopes, joys, aspirations and reversals–a drama in paint.

Though Irvin used vibrant, primary colours he did not wish for the colours to be associated with any particular emotion, since the way we experience colour is relative to and modified by context and time, and a similar approach towards the use of bold colours can also be observed in Li Lei’s work.

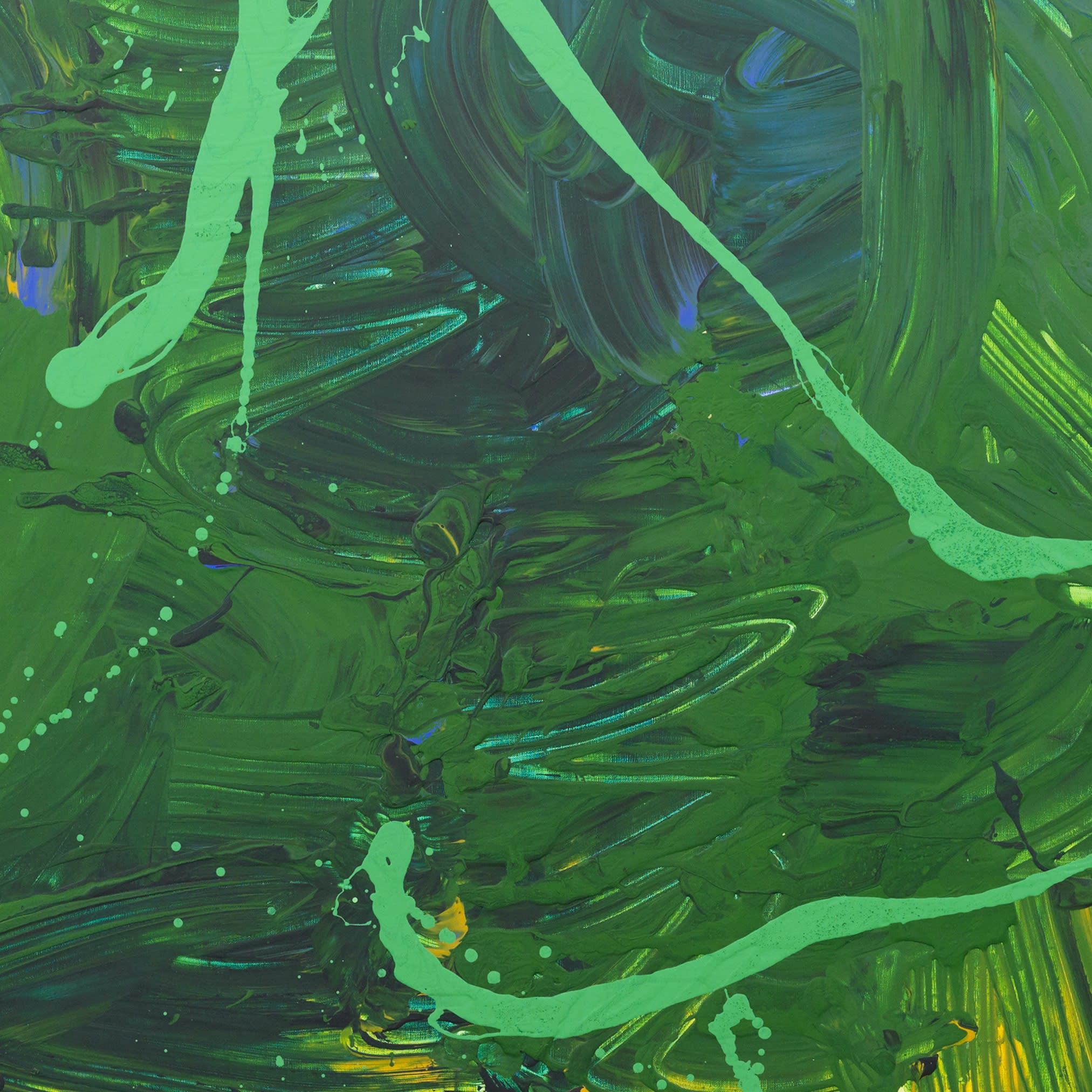

Li Lei has described his paintings as 'landscapes of the heart' and the improvised, winding lines, expansive primary colours and unconstrained, gestural brushstrokes, alongside the more considered, meditative brush marks within Mad Water- 20 illustrate the tension between Li's inner and external world. His painting style evolved from combining core concepts of Chinese culture and philosophy, and Western abstract art to depict the beauty of nature within the commotion of 21st Century society. No distinct forms can be identified. An abstract landscape, reminiscent of traditional Chinese ink landscapes, is created layer by layer with light and heavy, quick and slow strokes of the brush; through cold or warm, bright or dark colours; the thickness and curve of the lines. Li allows colour and brush reciprocity to reach a kind of tacit understanding, diminishing the traces of conflict between them and expressing the artists' inner world.

Li's spirit of contemplation evolved in the 1990s when he developed an interest in Buddhism, and through his practice began to question the deeper meanings of life, death and reincarnation. Whilst analysing the connection between the environment and self, Li came to realise that abstract art gave greater freedom and room for creative expression in comparison to traditional Chinese art, where life-like depiction of objects was the norm.

As Li Lei says: ‘Abstraction speaks right to the heart of visual perception, and the figurative essence is often obscured by representation.’

'Viewing his abstract painting is like looking at the calligraphy of Huaisu, with line and colour covering the whole surface of the painting, full of internal tension and rhythm, unrestrained yet quiet. There is poetry in the painting, a poetic quality surging in the flowing space; there is music in the painting, the solidification of rhythm in the dense colour fields'.

Extract from The Dialogue Between Poetry and Thought: On Li Lei ‘s Abstract Painting by Zhou Jiwu.