This ARTicle features an exclusive conversation between Ma Desheng and Calvin Hui, the Curator of Wish upon a Rock in 3812 Gallery. The artist talks about the exhibition and shares his early experience.

Calvin Hui (referred to as Hui): Mr. Ma, how do you interpret the theme of the exhibition, "Wish upon a Rock"?

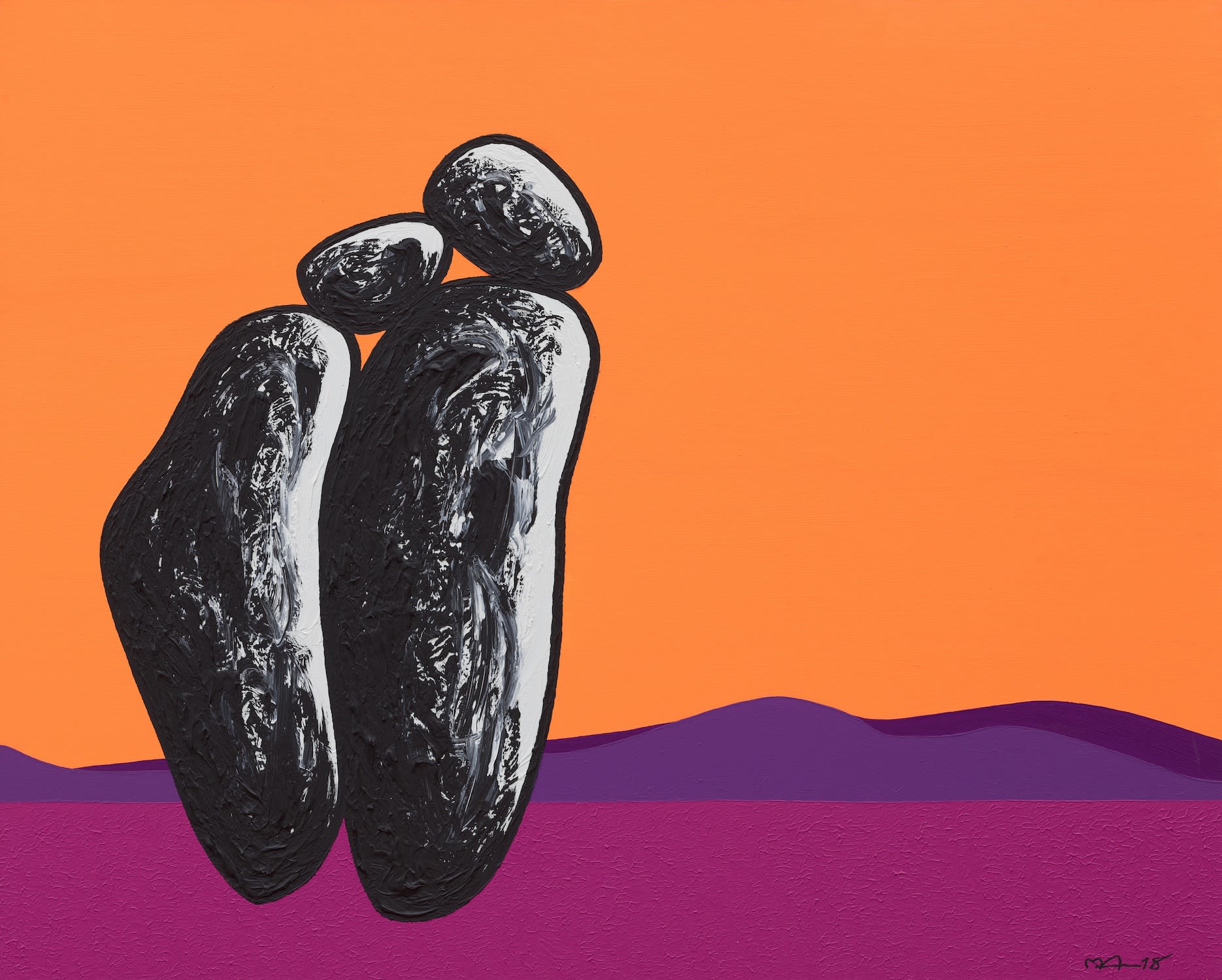

Ma Desheng (referred to as Ma): Through this exhibition, I aim to convey several important ideas. The rock has always played a significant role in my artistic career spanning several decades. It represents the power of daring exploration, the spirit of resilience, and the noble pursuit of an ideal life—much like the human-shaped stones showcased in this exhibition. These stones symbolise the qualities I strive for, resembling magnificent and sturdy mountains.

Furthermore, while a stone is a tangible object, time and space are abstract concepts. I have created a symbol that combines these elements, resulting in dream-like effects of existence and nothingness. This exhibition intends to explore these concepts, and I leave it to the audience to determine its success.

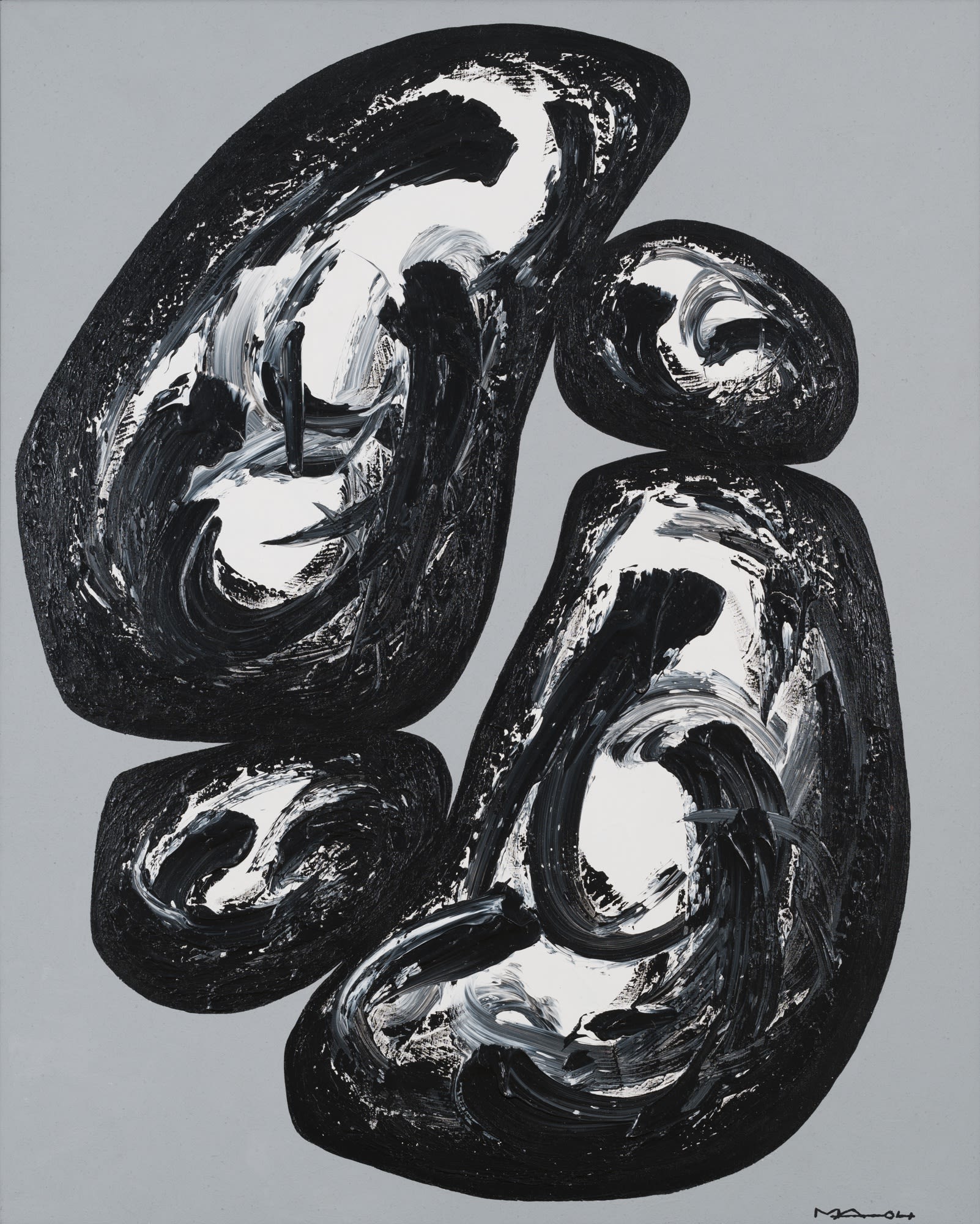

Gemini, 2004, Acrylic on canvas, 162 x 130cm

Hui: In the past, you had many exhibitions with the theme of rocks. Do you see any differences in this current exhibition?

Ma: In previous exhibitions held in Paris, London, and Hong Kong, the rock was more of a symbol with a sturdy and eternal image.

For this exhibition at 3812, I must say your curatorial essay is well-written and successfully captures my emotions. You have found a sublime perspective that offers a three-dimensional methodology of interpretation, and that is a significant difference. Specifically, it mentions the indestructible nature of rocks, the continual transformation between formation and fragmentation, and their eternal existence. It is similar to the experiences we encounter in life—whether happy or sorrowful, they are fleeting moments in time and space. However, people often get trapped and entangled in them. Therefore, I hope to use these rocks to inspire people and bring strength to our lives.

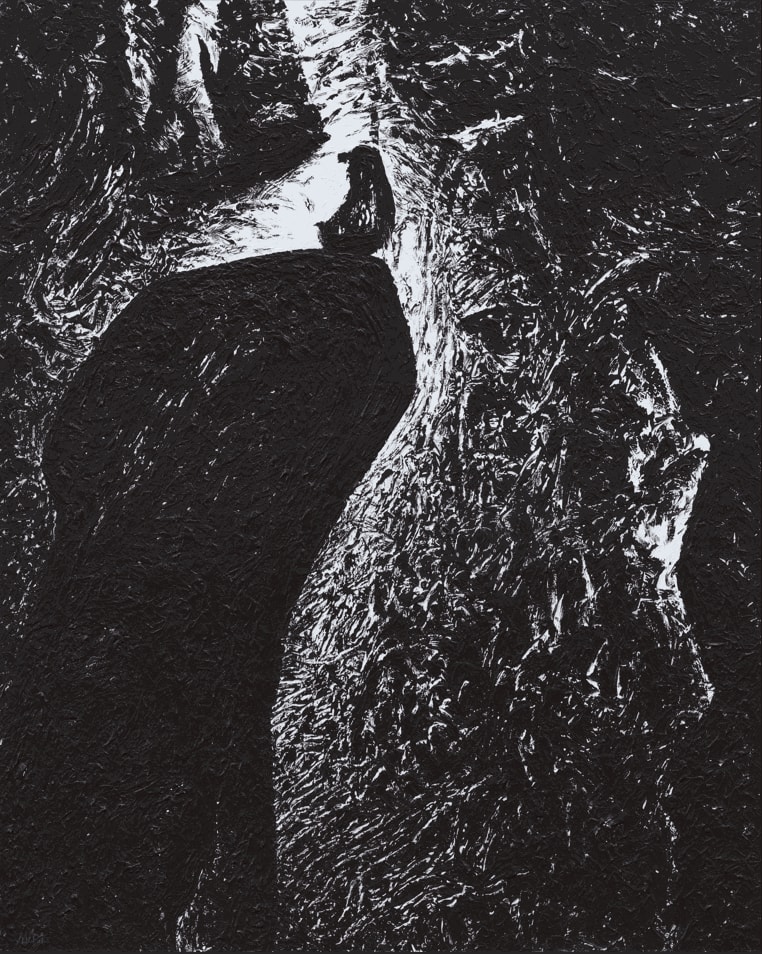

Unbridled Imagination III, 2002, Acrylic on canvas, 97 x 146cm

Hui: When did you start painting stones?

Ma: In around 1982, I started painting stones in Beijing using oil paint, creating surrealistic-representations of stones. After that, I took a break from the series and began painting abstract ink artworks. It wasn't until after spending two years in the hospital and undergoing eight years of rehabilitation that I returned to painting stones.

I have always been captivated by pebbles. When you hold one in your hand and slowly close your eyes, you can imagine it coming from a high mountain, tumbling down, rolling, and gradually becoming smaller. This idea came to me as a revelation, and I decided to paint stones. That's how it all began. In 2002, I started painting stones with acrylics, initially creating sketches and small works on canvas. Over time, I shifted towards larger works. The more I painted, the greater the sense of joy I felt.

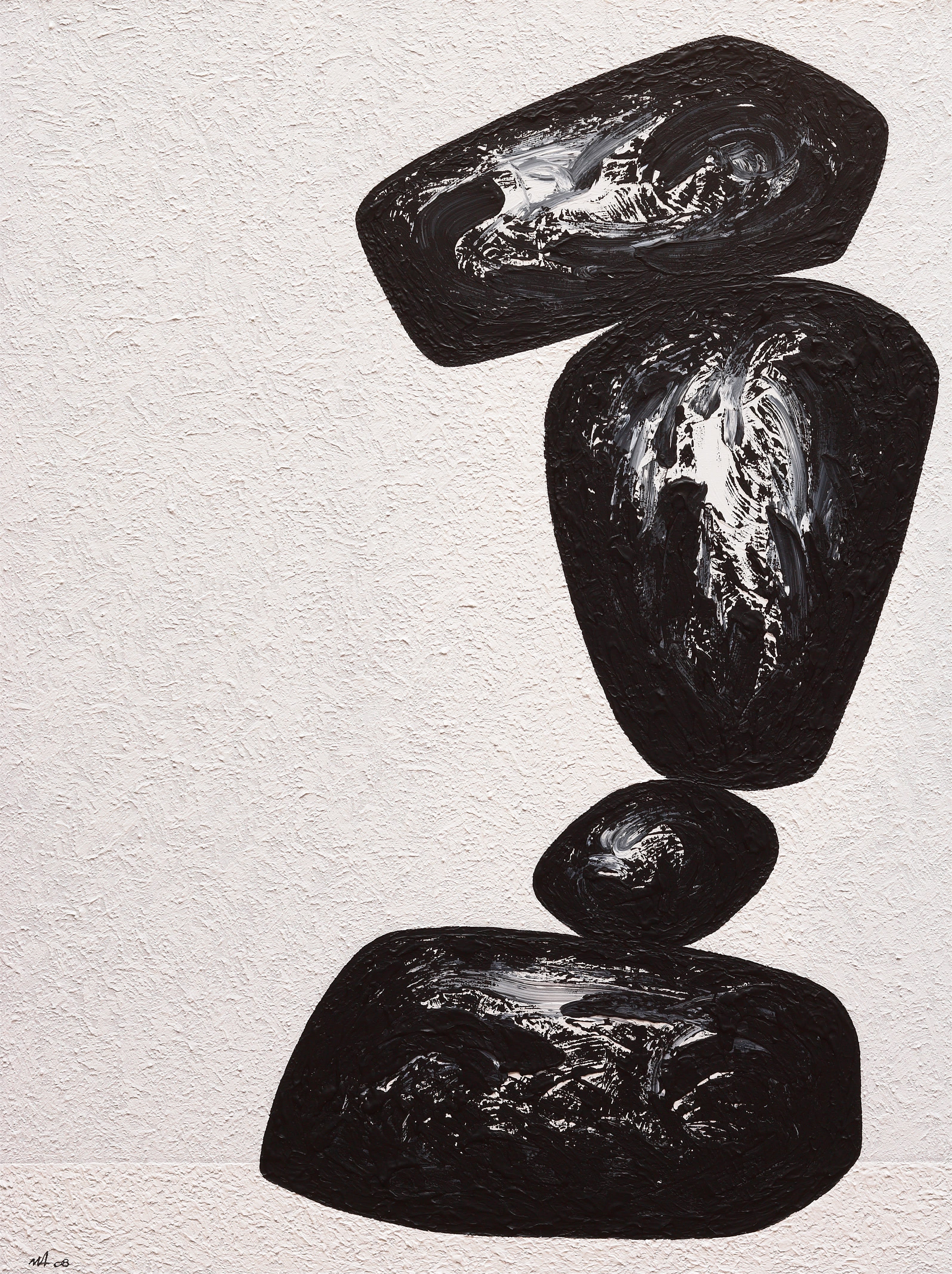

Faceted Stones, 1991, Ink on paper, 84 x 154.5cm

Hui: People interpret your stones in various ways. Some are from the perspective of Chinese culture, while others discuss them in terms of abstraction. I now understand that your creative process is sometimes spontaneous, integrating the stones with natural experiences to create a unique symbol. In 1976, right after the Cultural Revolution ended, you encountered Western abstract art and developed new artistic ideas. How did you come across these works during that time? What kind of influence did they have on you? Were there any particular artists who inspired you?

Ma: During that time, my classmates were admitted to art schools, and they could borrow magazines from school for me. It was through these magazines that I first came into contact with Western artworks, particularly sketches from the Soviet school, which had a profound impact on me. I found the works of Kandinsky, in particular, very intriguing. However, I still considered him a Western artist, and I believed I should focus on traditional Chinese culture. Subsequently, I began creating abstract works using ink. After completing large-scale pieces, I revisited tradition and created works that combined abstract and figurative elements.

Hui: In the 1980s, you transitioned to experimenting with ink. From what I understand, you were a passionate young artist with a grand vision, aiming to rejuvenate the long-standing tradition of ink art with a completely new artistic language.

Ma: When I first encountered Western art, it deeply moved me. It raised a question that is worth discussing, one that even Westerners often ask: why has Chinese ink art, which spans two thousand years, remained relatively unchanged? I wanted to break through this tradition by infusing my emotions, forms, and compositions into it, adopting a creative perspective of freedom to transform it.

Hui: By breaking free from the constraints of traditional ink painting, were you also aiming to revive Chinese culture?

Ma: I would like to address this question from the perspective of artistic creation. Artistic creation is essentially a process of breathing. It involves fully assimilating both tradition and elements of modern life, and then sincerely expressing oneself through art, like exhaling. It emphasises self-expression and innovation rather than replicating history.

During an interview at an exhibition in Switzerland, a journalist asked me about tradition, and I responded by saying, "To oppose tradition itself is tradition." Throughout history, it has been necessary to challenge tradition in order to create something new, and then that new thing becomes a tradition in itself. This is how history progresses, and people in each era must find a way to overturn tradition and create new things.

That period of my artistic journey was exceptionally important. I expressed my feelings and reflections on society and conducted artistic explorations of forms. This phase lasted for about 3-4 years, during which I worked during the day and created woodblock prints at night. It was a challenging time, and I simply viewed it as a way to channel my emotions, without considering fame or money. I have always been a sensitive person, perhaps due to my disability. Especially when confronted with injustice and unrighteousness, I dare to stand up and speak out. My early woodblock prints hold great value to me, as they carry a humanistic spirit, and I have always cherished them.

Hui: Indeed, during that time, you advocated for a spirit of artistic autonomy and creative freedom.

Ma: Yes, that is correct. I had two main objectives during that period. Firstly, it was about expressing genuine emotions, whether directed towards society, humanity, or individuals. There were no specific requirements in terms of form - it could be abstract or figurative - but the essential aspect was that it had to be diverse and sincere. Secondly, it represented the aspirations of the young generation for a brighter future in New China. In the specific historical and cultural context, we naturally had numerous visions and hopes. This sentiment was like a volcano that accumulated and eventually erupted.

Hui: Looking back at the "Star Group," it is evident that you and your peers pursued the authentic expression of personal emotions and had a grand vision for the future of New China. Are there any particular moments from that time that you would like to share with us? Your woodblock prints from that era were truly refreshing. Could you tell us more about them?

Ma: The "Star Group" holds great significance in the history of Chinese contemporary art. Beyond its art historical importance, it represents the passion, aspirations, and hopes of our generation. I have emphasised this in various interviews over the past few decades. During that time, the Chinese art scene was still heavily influenced by tradition and Realism. As young artists, we wanted to explore a more expressive and abstract style that returned to the essence of art, aiming to create a completely new art movement. I also firmly believe that art should have the freedom of expression, and artists carry a social responsibility to inspire and influence the audience, leading and promoting new waves of thought, rather than simply conforming to existing paradigms.

Hui: Why did you choose to go to France in 1986? How did you feel after your arrival?

Ma: I decided to go abroad in 1985 and chose France as my destination in 1986 primarily because of my eagerness for learning and exploration. It turned out to be a great choice. Let me share a story with you. In the early 1980s, shortly after I arrived in Paris, the municipal museum was collecting artworks. I submitted two ink paintings, and after some time, I received a letter along with 8,000 francs, informing me that one of my artworks had been acquired. At that time, it was a significant amount for me, and I felt immensely proud that my ink painting was being collected by a museum in France. In the Western art world, if they consider your work to be good, regardless of your origin, they will simply collect it. That's why I have always encouraged Chinese artists to actively engage in communication with the Western art world.

Hui: It must have been challenging for a Chinese artist to start a new life in a foreign country during the 1980s. What were your goals during that time?

Ma: My primary goal has always been to foster a society where cultural exchanges flourish and achieving Great Unity. I firmly believe that, at the core, there are no fundamental differences between us, except for the barriers imposed by borders and languages. I have experienced moments of profound connection and shared emotions while reading Western literary works, realising that our souls share commonality. We coexist on this Earth, and within our hearts, we can always find resonance and common ground. Therefore, regardless of the artistic medium, what truly matters is what you desire to express and how you choose to express it.

Hui: Over the past 40 years, you have made significant contributions to the art of freedom and expression. Do you still have any goals in terms of your artistic creations?

Ma: When I was younger, I had numerous aspirations, but now I no longer harbour any specific goals. Interestingly, the absence of pursuit has become my pursuit in itself, creating a paradoxical situation. This state of mind is sincere, akin to the Chinese saying, "Mountains are mountains, rivers are rivers."