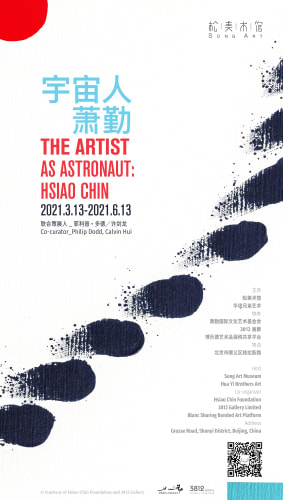

The Artist as Astronaut: Hsiao Chin: Song Art Museum Beijing

"The Artist as Astronaut: Hsiao Chin" is a large-scale retrospective exhibition of Post-war Chinese Abstract artist, Hsiao Chin (b. 1935), to be held at the Song Art Museum, Beijing from 13 March to 13 June 2021. 3812 Gallery is honoured to work with the Hsiao Chin Foundation as co-organisers of this exhibition.

Founder of the "Punto International Art Movement", Hsiao Chin is a prominent figure in the international Post-war art scene, active in both Eastern and Western art circles. Hsiao garnered recognition from the Western art world through his employment of Eastern aesthetics to create a distinctive style in the field of abstract painting. Co-curated by Calvin Hui (co-founder of 3812 Gallery) and Philip Dodd (British curator), the exhibition features 79 works, including paintings, ceramics and sculptures by the octogenarian artist across nearly seven decades of his career, from the 1960s to the present day and taking place across China, Europe and United States.

In addition to paintings, ceramics and sculptures, the exhibition will debut two immersive digital art installations by Hong Kong TECH-iNK artist Victor Wong (b. 1966), specifically made to accompany Hsiao Chin's works on this occasion. As an integral part of the exhibition, Wong's works on display demonstrate the impact and legacy of Hsiao Chin in the broader context of Contemporary art.

The Artist as Astronaut

BY Philip Dodd

When Hsiao Chin wrote to NASA in 1967, saying he wanted to be an astronaut and that the authorities ought to send an artist into space, he was being at once both profoundly contemporary and deeply traditional (as well as humorous). The cosmos has been part of the human imagination since ancient times - even if it had only been in 1958 that the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human being to leave the earth and travel into space. The earliest pictures of the cosmos date back around 18500 years ago to the cave paintings of Lascaux in France and Cueva del Castillo in Spain; and our ancient fascination with the cosmos and travelling through space is why space programmes are named after ancient gods and goddesses, whether Chang'e or Apollo.

Hsiao Chin was born in 1935 in Shanghai, eleven years before the first picture of the earth was taken from space and his long adult life stretches across the arc of actual space travel from Gagarin to the recent landing on the moon of China's Chang'e spacecraft. It is little wonder that the idea of the astronaut and of the cosmos is so important to him.

The recent resurgence of global interest in space, space travel as well as science fiction in so many forms - just think of the global success of Liu Cixin's Three Body Problem - offers us a fresh opportunity to understand how the idea of travel and space (both inner and outer) has shaped modern art in general and Hsiao Chin's work in particular.

(i)

Hsia Chin arrived in Milan in 1960 - at a moment when the city with its art, fashion, design and film was as powerful a centre of culture as was New York. From the point of view of this argument it is equally important that in 1962, the year that Hsiao Chin helped to launch the avant-garde movement Punto, Italy too joined the space exploration programme. This is of course not to suggest a cause and effect between space exploration in Italy and Hsiao Chin. It is just to recognise how much space exploration was in the air at the time when Hsiao Chin launched Punto.

Of more direct importance to Hsiao Chin was the figure of the great Italian artist Lucio Fontana, a friend and a great supporter. Fontana himself will be forever associated with notions of Spacialism (Spazialismo) - with the practical ways of making an art that interrogated the mysterious properties of space. In the late 50s, just after Gagarin's space trip, Fontana moulded and shaped from terracotta forty-four organic spheres, containing gouges and clefts, under the title of Nature. Fontana said 'I was thinking of those worlds, of the Moon with these… holes, this terrible silence that causes anguish, and the astronauts in a new world'. For Fontana these spheres, allowed him to 'represent nothingness! This is the death of matter, pure life philosophy!' were his words.

Again, the point is not emphasise that Hsiao Chin was influenced by Fontana (although he is happy to acknowledge the debt). What is interesting about Fontana's words is rather that they seem to refer to Eastern philosophy ('represent Nothingness'). Certainly the merest glimpse at Laozi shows how important space was to the ancient philosopher ('Shape clay into a vessel. It is the space within that makes it useful'), for all the world as if Laozi were Fontana's teacher.

(ii)

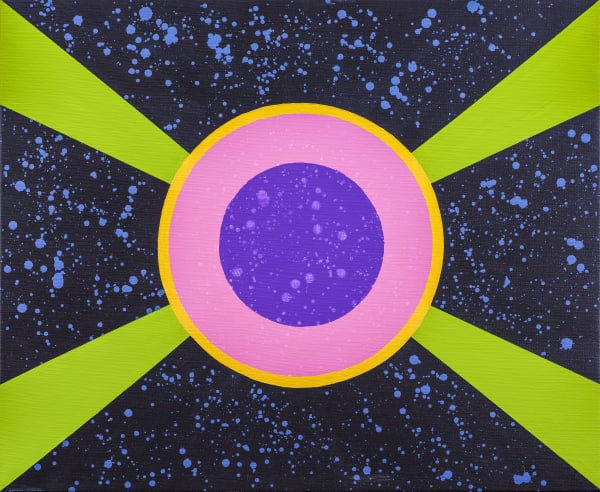

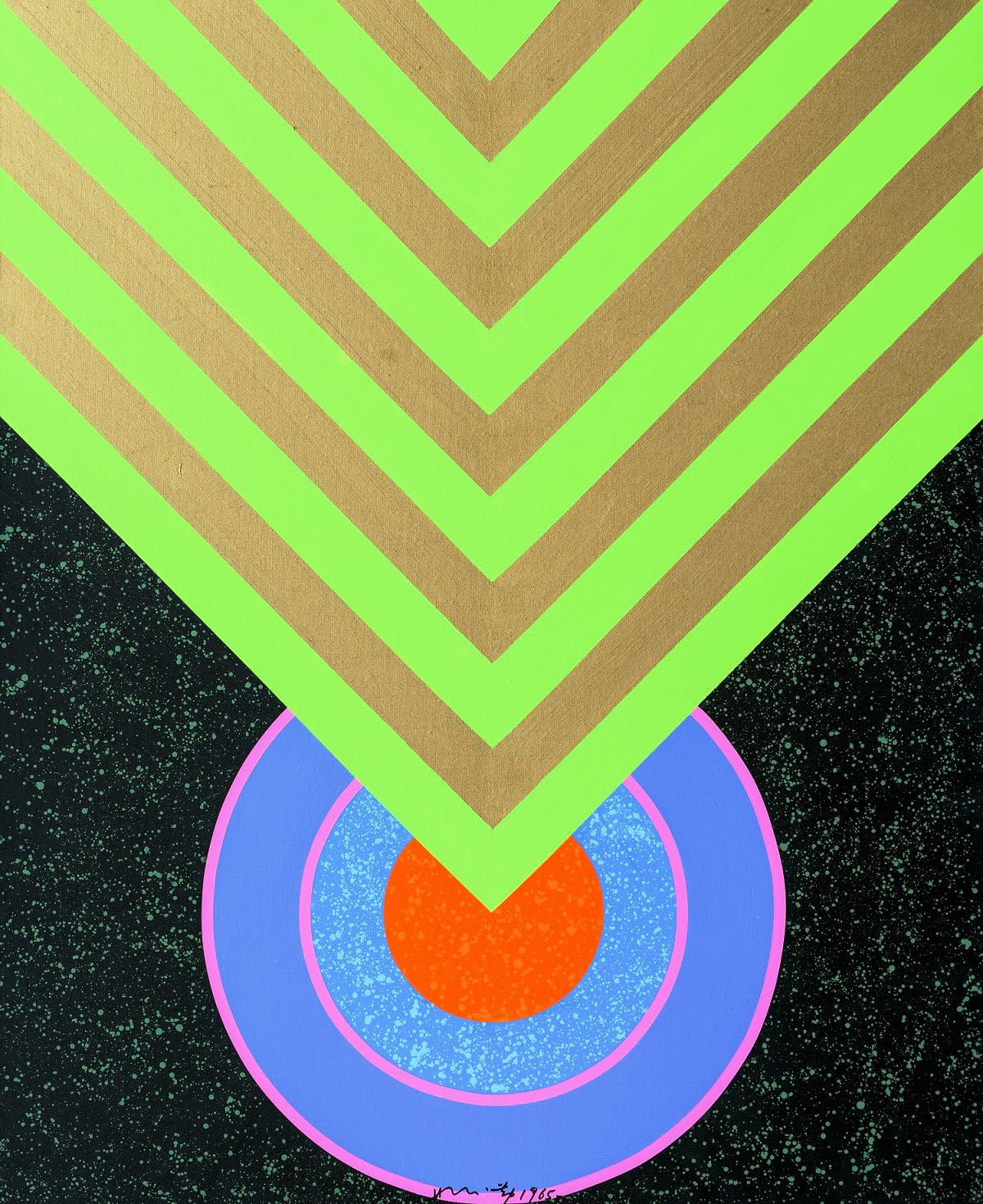

One of Hsiao Chin's most important and most remarkable works of the 1960s is Power of the Light (1965). It is a quite large vertical painting including geometrical shapes - what looks like part of a rhombus and a series of concentric circles, one inside another. There is depth to this painting, the rhombus seems to lie in front of the circles which themselves give way to what in 1965 must have looked like an image of black outer space, punctuated by blue dots (or faint stars).

Once we have described the painting, how are we to understand it, this abstract painting? At one level it seems to be a way of trying to represent the cosmos; it seems the most contemporary of paintings (both in 1965 and now). But at another level the rhombus and the circles lead the eye into the darkness 'beyond' them. It is as if the rhombus - and in Chinese philosophy the square is the earth - is a curtain partly masking infinity beyond. Is this the 'nothingness' that Fontana referred to and that is deep in Eastern philosophy? Power of the Light is a most remarkable painting - one that uses the iconography of the contemporary world, of the discovery of space travel, to provide an image of both outer and inner space. In science fiction, outer space is often used to explore inner space - but it is rare for a 1960s visual artist to do so. This is a painting that conjures up spaces within spaces (look at the cosmos inside the circle). It is a painting which could only be made by someone who had access to a cultural and artistic language that could draw from East and West, from classical and contemporary. It is one of the features of Hsiao Chin that disrupts the either Asian or European narrative - and makes him such a distinctive artist, both then and now.

(iii)

Hsiao Chin once said, humorously, that he did not belong to this world but is a 'Citizen of Outer Space'. The great American composer and jazz musician Sun-Ra, a contemporary of Hsiao Chin's, said the same. For Sun Ra, extra-terrestriality was his way of trying to distance himself from 50s and 60s white America and to insist on black identity at a time of the struggle for civil rights.

Hsiao Chin's interest in outer space is other: it can in part be traced back to his attachment to Laozi and the Tao which were both profoundly suspicious of materialism and commercialism, and which he rediscovered 8in Milan in the 60s.

My sense is that Hsiao Chin's imagining himself as a citizen of outer space was his singular way of rejecting the commercialism and materialism that saturated and still saturates the world. To put it this way, to imagine himself as an 'alien' gave him a point of view beyond this world and its story of worldly success; it allowed him to imagine in his paintings new worlds, to explore inner and outer space.

(iv)

Hsiao Chin has never stopped developing and expanding the language he forged in the 60s - for example, the sun and refracted light remain important to him. His life has been a matter of departures and arrivals, exploring new worlds. Another traveller, TS Elliot, whom I referred to earlier once wrote in his great poem the Four Quartets (itself influenced by Buddhism) that

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time

Hsiao Chin's fascination with the astronaut and with space seems to me to be his way of saying in art what Elliot said in words. His greatest achievement has been to forge a language, both classical and contemporary, to imagine inner and outer space - to envision the universe anew and our place in it.

Visit the Song Art Museum website for more information and tickets.

Download the Exhibition Catalogue

-

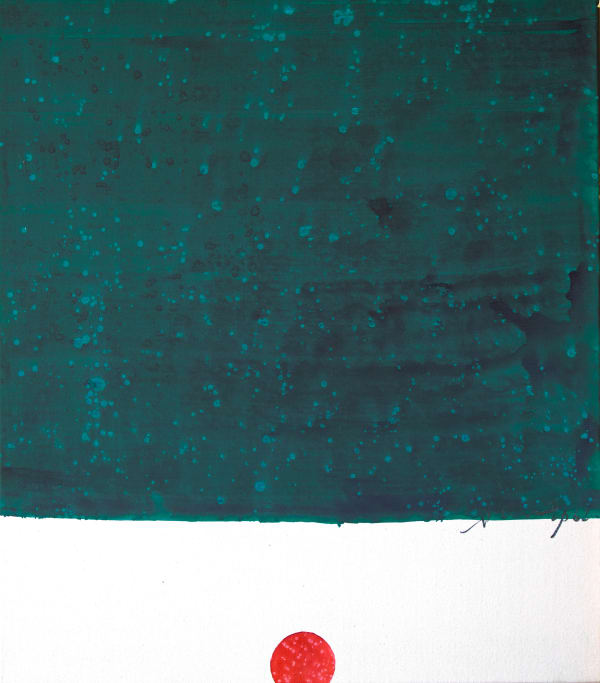

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, The Beginning of Tao-2《道之始-2》, 1962

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, The Beginning of Tao-2《道之始-2》, 1962 -

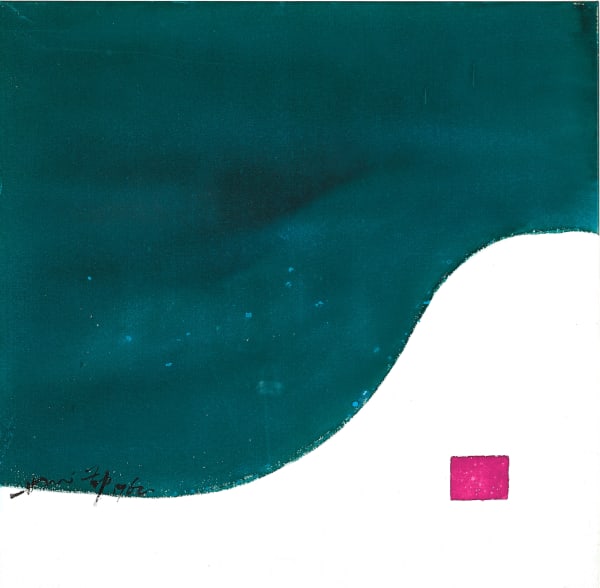

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Il silenzio《靜》, 1962

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Il silenzio《靜》, 1962 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, La Forza《勁》, 1962

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, La Forza《勁》, 1962 -

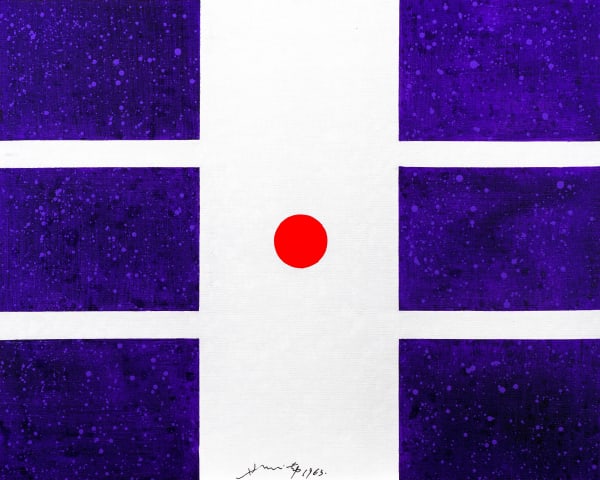

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Great Earth《大地》, 1963

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Great Earth《大地》, 1963 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Movement-2《動態-2》, 1963

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Movement-2《動態-2》, 1963 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Dancing Light-5 《光之躍動-5》, 1963

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Dancing Light-5 《光之躍動-5》, 1963 -

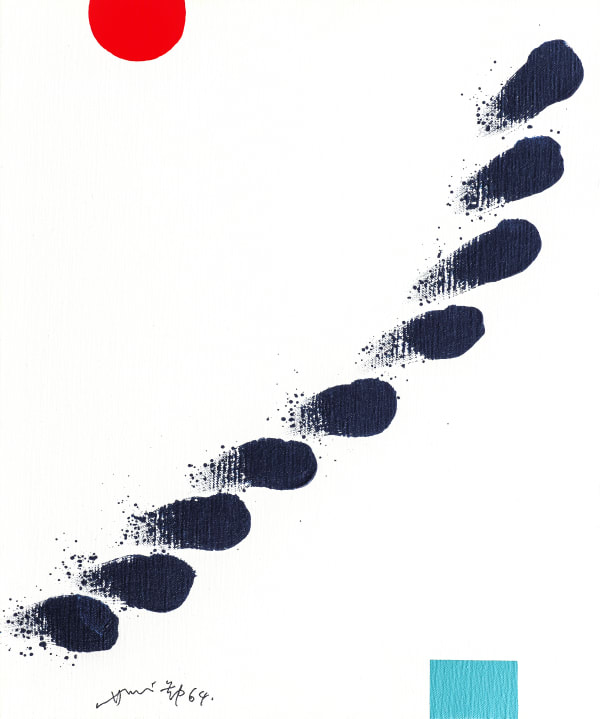

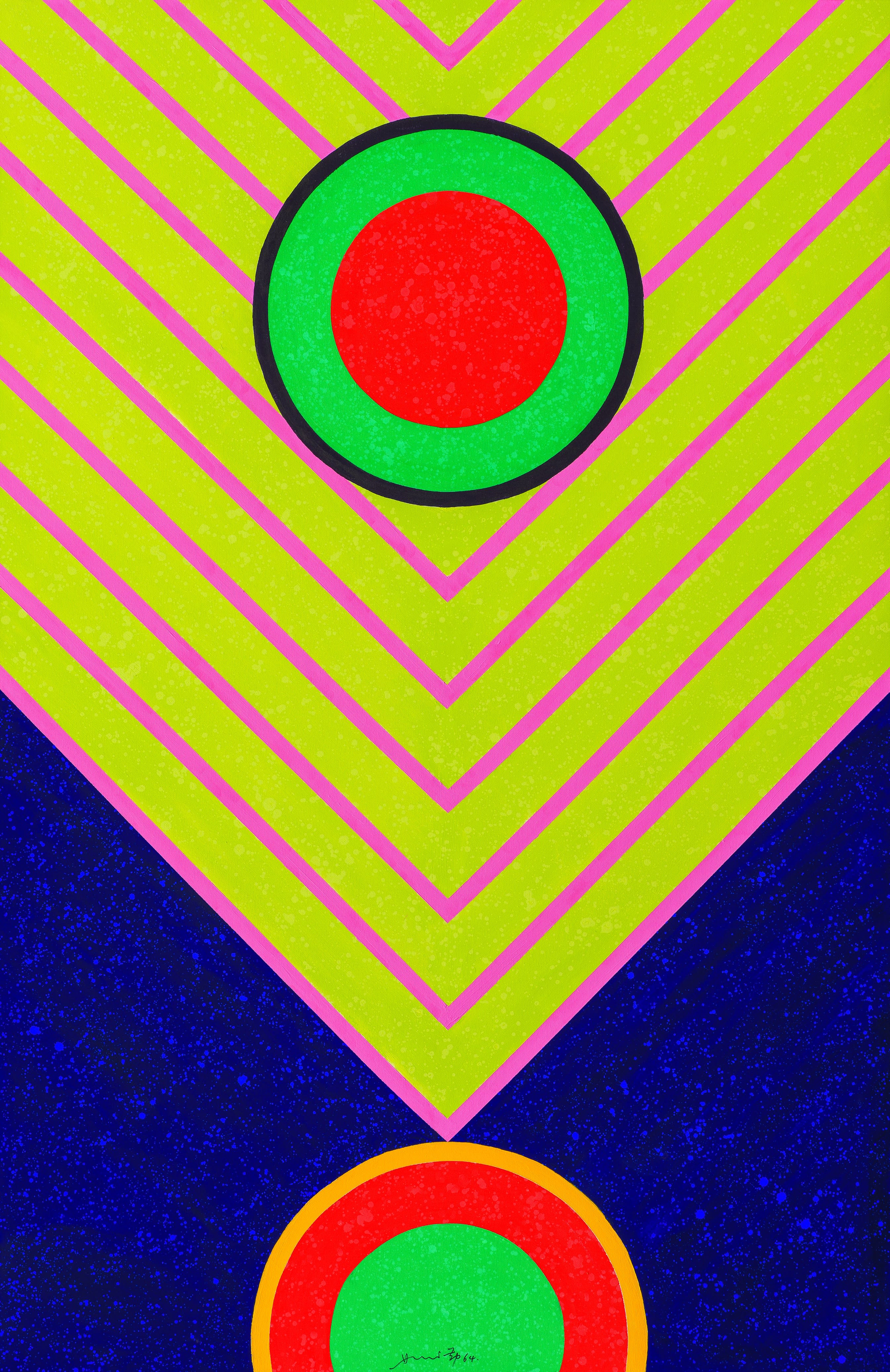

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Cause Of Life-1《緣生-1》, 1964

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Cause Of Life-1《緣生-1》, 1964 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Radiation (La proiezione)《放射》, 1965

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Radiation (La proiezione)《放射》, 1965 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, In the Depth of Darkness (Nel profondo delle Tenebre)《在黑暗的深處》, 1965

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, In the Depth of Darkness (Nel profondo delle Tenebre)《在黑暗的深處》, 1965 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Nero《黑》, 1967

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Nero《黑》, 1967 -

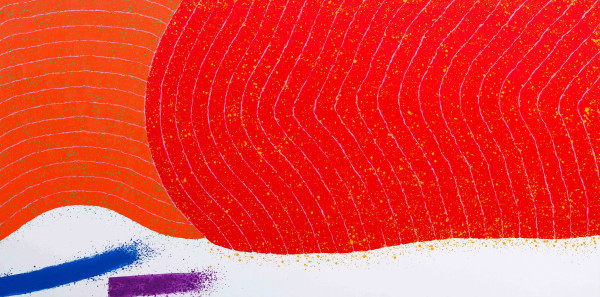

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Poised to Roar《趨翔》, 1974

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Poised to Roar《趨翔》, 1974 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Great Understanding is Without Words《大悟無言》, 1977

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Great Understanding is Without Words《大悟無言》, 1977 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Chi-297《炁-297》, 1983

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Chi-297《炁-297》, 1983 -

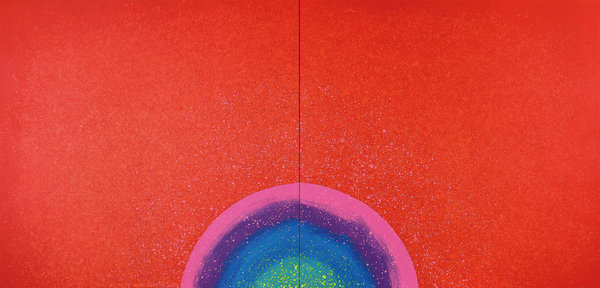

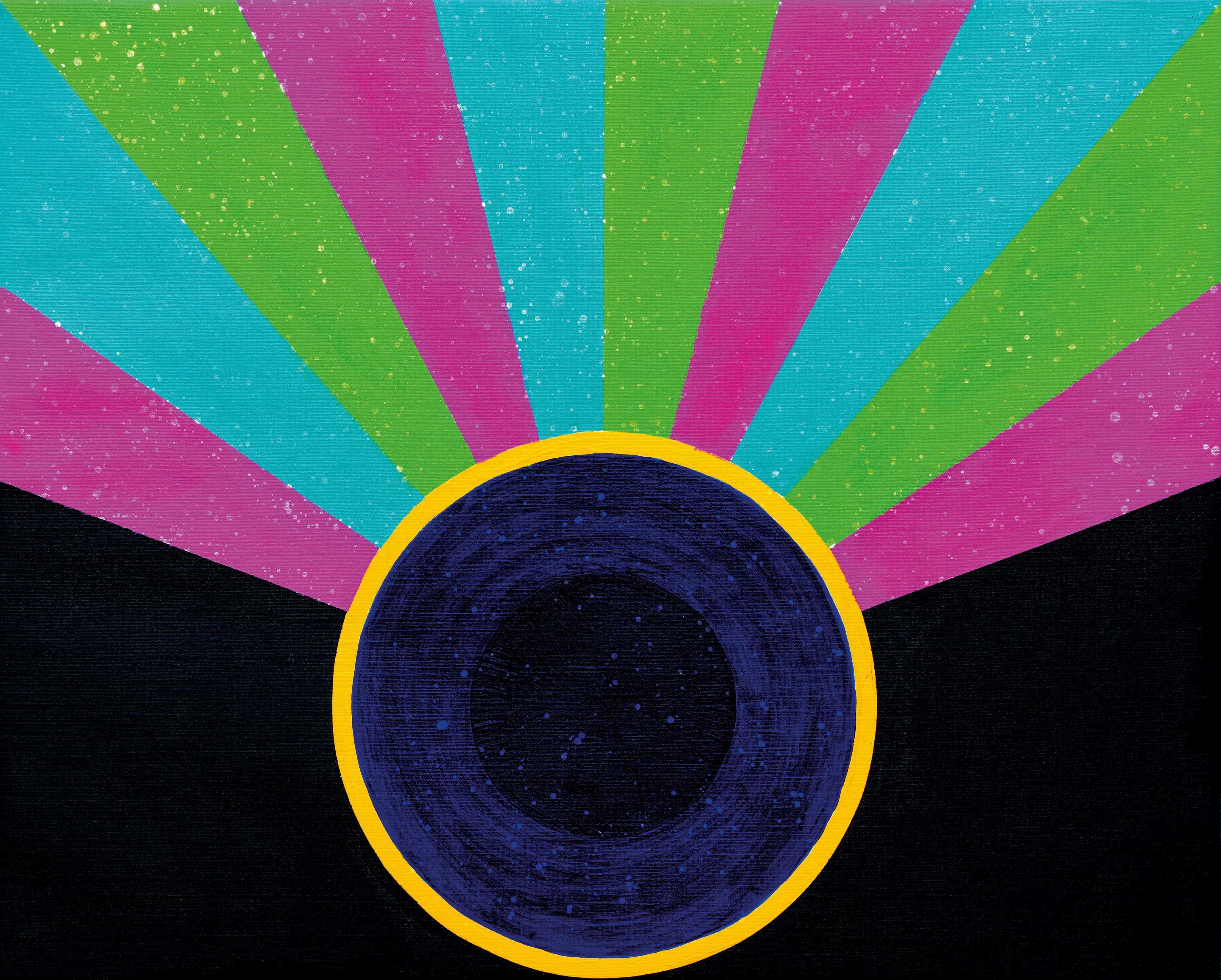

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Bright Light-Homage to Ascendance《明光-向昇華致敬》, 1990

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Bright Light-Homage to Ascendance《明光-向昇華致敬》, 1990 -

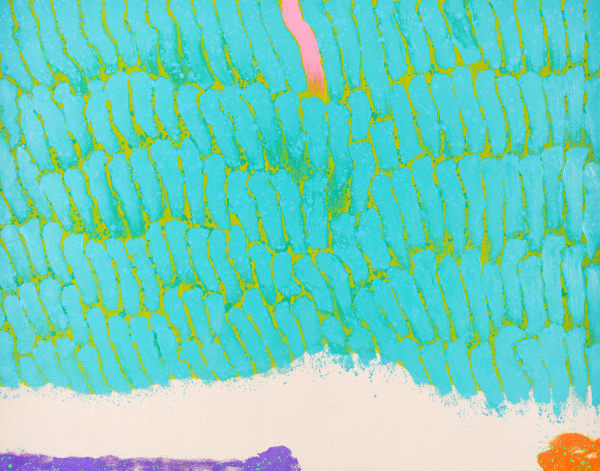

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Transcending the Eternal Garden-2《超越永久的花園-2》, 1993

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Transcending the Eternal Garden-2《超越永久的花園-2》, 1993 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Meditazione del superamento del grande soglia《超越大限之冥想》, 1996

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Meditazione del superamento del grande soglia《超越大限之冥想》, 1996 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Force of the New World-6《新世界之能-6》, 1996

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Force of the New World-6《新世界之能-6》, 1996 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, La forza di Vita-1《生命力-1》, 1999

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, La forza di Vita-1《生命力-1》, 1999 -

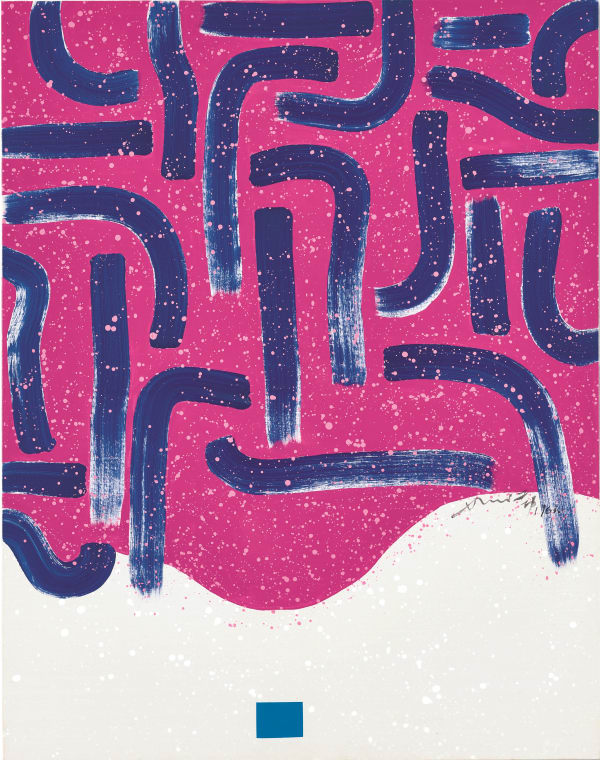

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Il riservo dell'inverno/Canto diquattro stagione (1,2,3)《冬藏之一、二、三-四季禮讚》, 2008

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Il riservo dell'inverno/Canto diquattro stagione (1,2,3)《冬藏之一、二、三-四季禮讚》, 2008 -

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Love of the Universe《宇宙之愛》, 2010

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Love of the Universe《宇宙之愛》, 2010 -

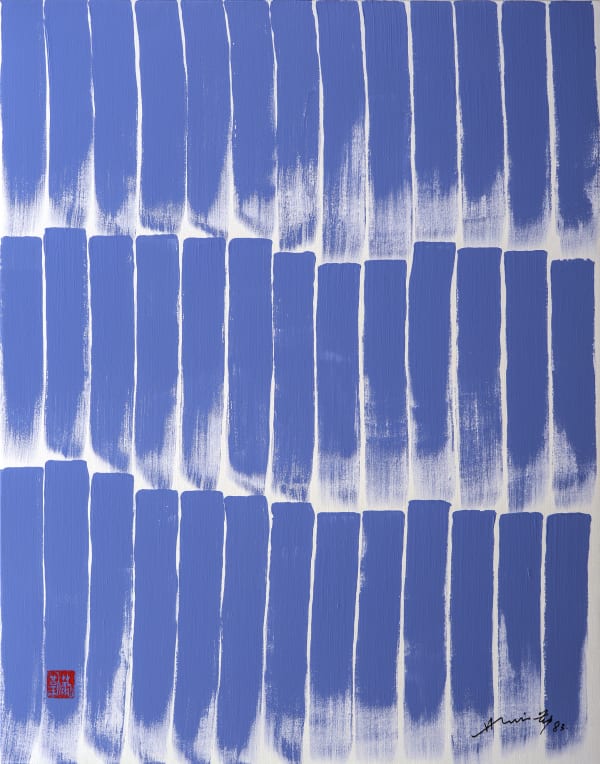

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Inner Joy《內悅》, 2014

Hsiao Chin 蕭勤, Inner Joy《內悅》, 2014