Follow Mark Jone's interview with Hsiao Chin on Christie's magazine to experience the epic life journey of the artist Hsiao Chin - from China to Europe, anger to focus, and grief to acceptance, which is reflected in his radiant, uplifting paintings.

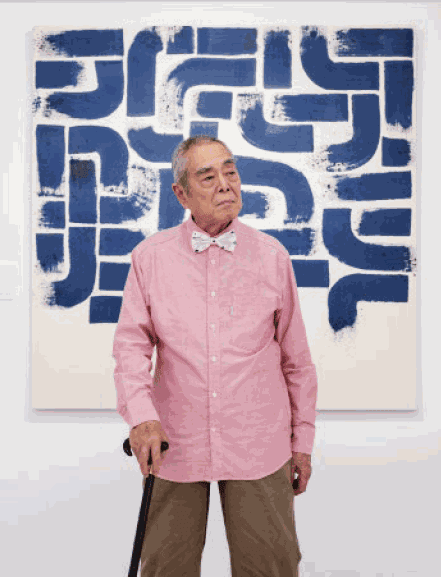

Hsiao Chin with Movement Energy, 1985

‘Li Chun-shan taught me how to think. Everyone knowshow to paint. It is very, very difficult to think’

It’s an irresistible opportunity. I am leaving the foundation dedicated to one of the great abstract foundation dedicated to one of the great abstract artists, Hsiao Chin, with the artist himself. On the wall is a rare image in his oeuvre: a self-portrait.

So, of course, I ask if I can get a photograph of him next to himself. No problem. The Hsiao Chin of 2020 is 85 years old. He’s a little tired after our interview – we have talked for most of the afternoon – but he’s as jovial and courteous as when we were first introduced.

The Hsiao Chin of 1955 is moody: his lips pursed, his gaze challenging the viewer and thus himself, the sitter, the painter, the subject. The portrait seems to ask: what will you become?

At first glance, Hsiao has become a typical friendly Chinese uncle: stooped yet strong, bushy eyebrows, twinkling eyes, close-cropped hair. Then again, he is wearing a hot-pink T-shirt, green cargo pants and beads wrapped in a thong around his wrist. The effect is more bohemian than avuncular.

In 1955, Hsiao was something of an angry young man. He’d just launched Ton-Fan (‘the eight outlaws’), a group of artists based in Taiwan looking to define Chinese modernism for a weary, post-war China and Taiwan, where the only art that interested the authorities was the patriotic kind.

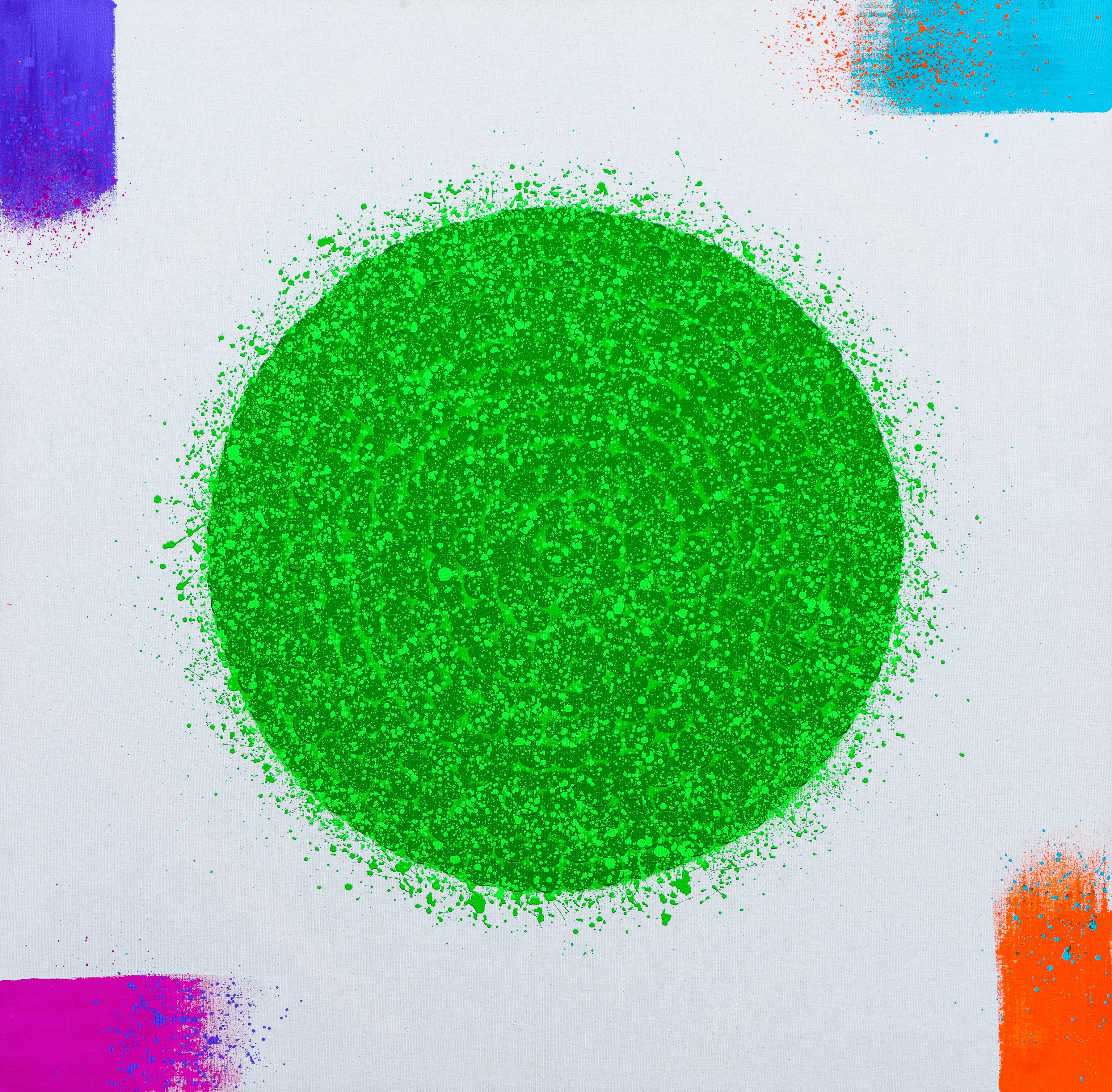

Hsiao Chin, The Eternal Garden-82, 1997 (detail), Acrylic on canvas, 110 cm x 90 cm. © Hsiao Chin Foundation.

Like so many Chinese of his age, Hsiao is the product of loss and displacement. His mother and father, the latter a distinguished music teacher who founded the Shanghai Conservatory of Music in 1927, had both died by the time he was 10 years old. He was taken to Taiwan with relatives at the end of the civil war and separated from his younger sister, who went to live with a different branch of the family in China. She would end her life in a Beijing institution. He would allude constantly to that sense of separation in his work: his paintings often feature sibling symbols as close and distant as a planet and its moon.

It was an inspirational teacher in Taipei who set Hsiao on his way. The artist Li Chun-shan, who had studied with the great modernist Foujita in Japan, took Hsiao and a small group of art-mad friends for classes at his studio on Andong Street. ‘He taught me how to think,’ says Hsiao. ‘This is very important. Everyone knows how to paint. It is very, very difficult to think.’

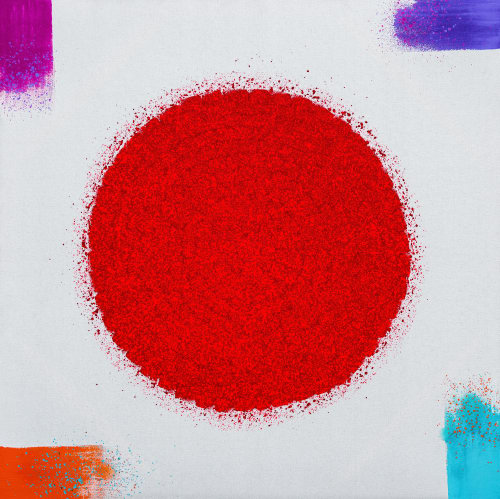

Hsiao Chin, Samantha nel Giardino Eterno-7, 1999 (detail), Acrylic on canvas, 140 cm x 110 cm. © Hsiao Chin Foundation

Hsiao’s career choice was set, although his artistic milieu was discouraging. Fortunately, Taiwan’s Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek had cultivated ties with the Spain of Generalissimo Francisco Franco, and in 1956, funded by a scholarship, Hsiao found himself on a boat from Hong Kong to Madrid to study art.

He disliked Madrid but loved Barcelona. So he moved there, sacrificing his government grant. In the years that followed, he supplemented the sales of his art by freelancing as a curator and journalist, promoting his own work and that of his friends, and, through the Ton-Fan group, propagating a version of uniquely Chinese modernism. He worked hard, but also revelled in the life of the Catalan city and the islands of Mallorca and Ibiza. ‘It was kind of a wild place for artists,’ he says, happy at the memory.

Much of his early work is suffused with Mediterranean light, intensity and colour. Around 1960, he also moved, decisively, from the layered density of his early abstract oils to a place that is serene, graphic and ethereal. That serenity has characterised his work ever since, even in his lone venture into political art, his glowering Tiananmen Square Protests series of the early 1990s.

The advent of Hsiao’s mature style coincided with his move to the Brera quarter of Milan (Barcelona felt ‘a little bit too isolated from the rest of Europe’). Here, his work attracted the attention of two venerated modernists, Antonio Calderara and Lucio Fontana, and he was taken on by the Marconi gallery. And while Ton-Fan had a character that was adolescent, rebellious and specifically Chinese, Hsiao’s next group, Movimento Punto, launched in 1961, was expressly cosmopolitan: it included Calderara, Japanese sculptor Kenjiro Azuma and Chinese artist Li Yuan-Chia.

Like so many movements, it arose out of an opposition. The Art Informel movement had been a dominant force in the salons and academies for the past decade, championing a free, improvised, unpremeditated relationship between the artist and the work. Hsiao and Calderara argued instead for rigour and forethought: having a point, in both a conceptual and technical sense – the point being a dot of colour or light that brings the concept into focus.

Hsiao had a different point of reference from his European counterparts. His abstracts were inspired less by colour theory and what were, to him, the ‘cold’ methods of op art than by his increasing absorption in Taoist and Zen Buddhist theories of flow and energy.

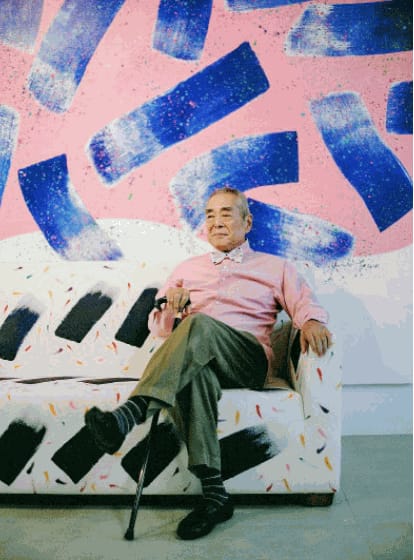

Hsiao Chin, Dancing Lights, 2018 (detail), Acrylic on canvas, 200 cm x 410 cm. © Hsiao Chin Foundation

The Punto canvases remain his biggest sellers at auction. As the 1960s went on, the softness and luminosity of these Mediterranean-influenced abstracts became sharper, more geometric – inspired now by his voyages in outer as well as inner space.

‘In 1967, I applied to be an astronaut,’ Hsiao reveals. ‘I am very interested in space projects, so I write a letter to NASA. The conditions are you have to be a citizen, you have to be in good health, you must be 40, 45, and you have to be a scientist. Well, I am not a scientist. But I said, “You should send an artist to the universe!” They said, “You are not qualified.” No sense of humour.’

One alien planet Hsiao found impossible to conquer was the New York art world. For a while he taught and hung out in the Hamptons with De Kooning and other ‘rich artists’, but by the early 1970s he was back in Milan.

In 1962, Hsiao had married the Italian artist Pia Pizzo. They were, he says, more successful collaborators than spouses and divorced seven years later. Their daughter, Samantha, was born in 1967. After 1980, he made several visits back to China, where he was finally reunited with Xuezheng, his sister. In 1990, while visiting South Korea, he received the news that Samantha had died after a domestic accident.

For the best part of a year, Hsiao was unable to work. When he returned to the studio, it was to his most sublime and overwhelming series, To the Eternal Garden. One of the larger canvases hangs in a room in the Kaohsiung house owned by Maggie Wu, the head of his foundation. Bars of luminescent blue rise from the red chi, or life spirit. One bar is coloured pink. It represents Samantha’s soul. Throughout the series, the sense of energy flowing eternally upwards is irresistible and heart-stopping. The effect is anything but elegiac. ‘Now I have been through such heart-wrenching experiences and understand the nature of it,’ he wrote in 2013, ‘it finally dawns on me that life is eternal.’

In 1996, Hsiao returned to live in Taiwan with his new wife, the Austrian soprano Monika Unterberger. He has continued to explore the universe through his Endless Energy series. Radiance has replaced geometry. And he alludes to the words of Joan Miró: ‘It is not easy work. You might start easy, but it’s difficult to stop: and recognise the right moment.’

This helps to explain why his abstract works produce such an emotional effect. They bathe you in light and colour. But stronger still, there is, in all his canvases and mosaics, a sense of acceptance and completeness that speaks to something elemental. It never seems as though there is a superfluous dot, stroke or device: all is as it should be.