Extract from Chapter 5

© Tate 2000

Reproduced by permission of the Tate Trustees.

Through the rest of the 1960s and into the 1970s, Frost produced a body of work which was remarkable for the formal simplicity and openness of the paintings. In both of these qualities, he was helped by a new medium, as he began to paint, primarily, with acrylics.

Acrylic artists' paints had emerged in America during the 1950s, and gained prominence at the beginning of the 1960s, as their physical qualities suited the desire for the large, flat areas of unmodulated colour of Post-Painterly Abstraction. Acrylic emulsions were produced in Britain from 1963, but Frost did not encounter them until they were supplied to him at San Jose. Unlike oil, acrylics are quick-drying, so one painting can be worked on at a time, and they can be thinned without losing the intensity of the pigment; thus a strongly coloured, but thinly painted, surface can be achieved. These qualities complemented the new 'heraldic' character that Frost had identified in his recent work.

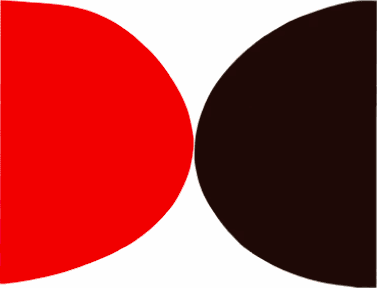

Though he would occasionally revert to oil, Frost embraced the new paints with enthusiasm and produced a large number of pictures which were characterised by strong, unmodulated colour arranged in a variety of forms. In contrast to the delicately expressive surfaces of his earlier work, and the combination of different qualities of paint - thick and thin, dabbed and dripped - Frost's work came to ride simply on colour and on the shapes that contained it. One of the first of this type was a series of paintings made up of red and black quadrants on a white field (fig.42). Though these were clearly a development from the laced boat/body works of 1962-3, the simple flat forms also recalled the art of Ellsworth Kelly that Frost had seen in New York in 1960. While the tension of simple forms brought into close conjunction had become even more important, Frost acknowledged a possible anthropomorphic reading when he nicknamed these works 'Mae West', referring to the buxom film star.

Fig 42. June Red and Black, 1965, Acrylic on Canvas, 244.S x 183.5cm

The sparing arrangement of these suggestive shapes on a large canvas continued. In Red, Black and White (fig.2) two curved, breast-like forms are held in tension as the narrow strip of white between them becomes the most active part of the composition. With such works, Frost reached new heights of abstraction, as the shapes are stripped of much of their allusive meaning and reduced to large areas of pure colour that enwrap and absorb the viewer. Conversely, from the Mae West paintings, Frost developed a series of works in which the ground became the active element, so that what had been merely the space between the forms was now a curvaceous cross. In Spring (fig.43), the tapering arms of the cross reach outward to the edges of the composition, with a variety of other forms - chevrons, a collection of sinewy lines, and a rectangle like an inset picture - activating the periphery and space of the picture.

Red, Black and White, 1967, Acrylic on canvas, 198 x 259cm

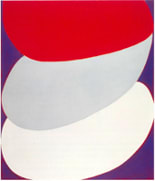

If these works were primarily concerned with the distribution of discrete forms within a space, others of the period also rested upon the shapes themselves. Red and Three Blues (fig.44), for example, relies for its effect on the soft appearance of its forms, which seem to tumble down and bulge outwards, as if straining the edges of the canvas. Using the most simple of colours, Frost seems to play with the viewer by disturbing the stasis that one would expect in a picture made up of three shapes, with the implication of an internal dynamism. The creation of an illusory massiveness to the forms was yet more apparent in a series of Suspended Forms paintings (fig.46), in which a sense of gravity is conjured up by the shape of the different areas of colour. These became increasingly literal, as he made collages on the same theme and then produced a group of brightly painted, stuffed, canvas tubes which literally responded to gravitational forces.

Fig 44. Red and Three Blues, 1970-1 Acrylic on canvas 213.4 X 182.9cm

Fig 46. Suspended Forms 1967 , Acrylic on canvas 182.9 X 132.1

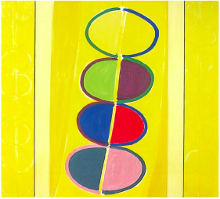

Over the years, from the 1960s and through the 1970s, Frost employed a variety of compositional themes: various means of creating a sense of movement within the static confines of the canvas. Certain groups of works, their titles suggested, had some relationship to external sites or events, such as a group of paintings with forms tilting to one side, which he associated with a visit to Pisa, or another in which a host of brightly coloured shapes follow a slightly curved vertical, which were apparently inspired by the moonshots of the early 1970s (fig.47). Whatever the apparent source or reference, all of these works really used shapes as vehicles for colour, as Frost explored the possibilities of intense hues and their relationship to form. Later in the decade, he returned to more geometrical arrangements in which the bright, discordant colours became the dynamic elements in a stable structure (fig.45).

Fig 45. Summer Collage, 1976, Acrylic and paper collage on canvas 215.9 x 155.1 cm

Fig. 47. Yellow (Moonship) 1974, Acrylic on canvas 215.9 X 241

During the 1960s and 1970s, Frost's brash colouring echoed aspects of popular culture, while, at the same time, his persistent commitment to painting distanced him from the mainstream avant-garde. The 1960s, with the advent of minimalism, Fluxus and conceptual art, had seen performance and text rise to dominance over traditional media and practices, in a reaction to the high-art values of abstract painting and sculpture. The continued production of an art predicated on the theories and values of 1950s painting ensured Frost's relative marginalisation, until a recovery in the 1980s, following the revival of painting.

All images courtesy of the Estate of Terry Frost